Every other year the Holland Animation Film Festival shows a selection of some of the best independent animation films of the past two or three years as well as a number of retrospectives and thematic programs. If I am around I like to spend a day or so at the festival to have my mind stretched and my imagination triggered. With several hundreds of films in various categories it is impossible to cover the entire festival, so here are some personal highlights of this year's festival.

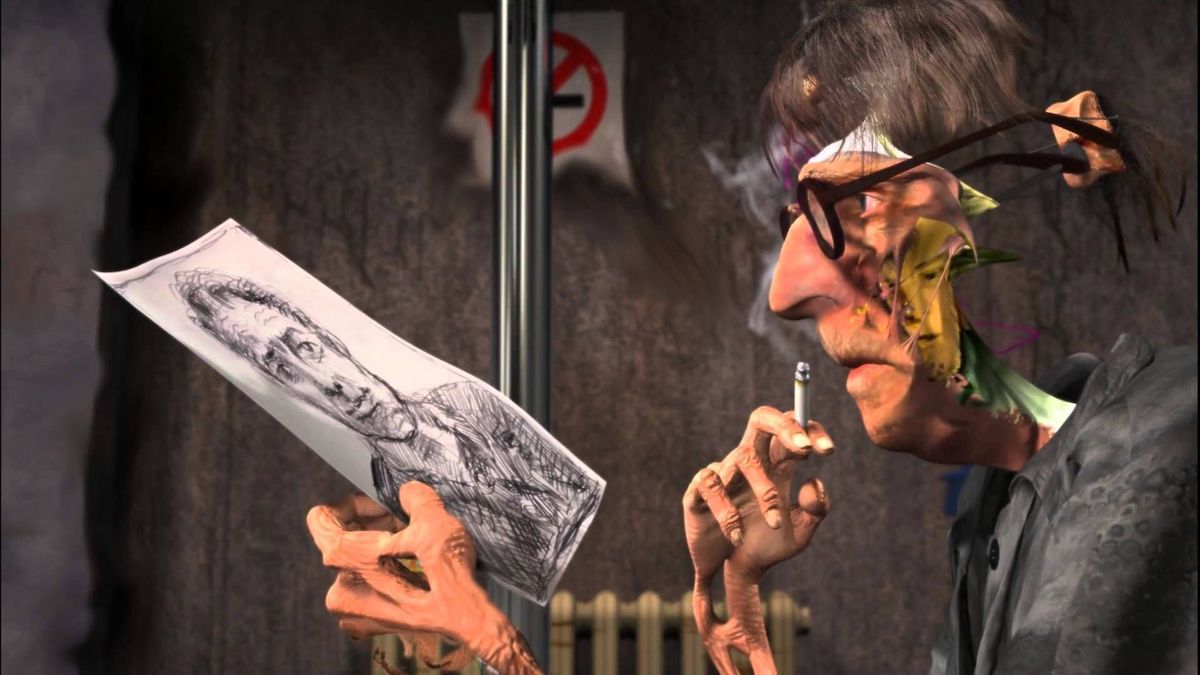

"Ryan" by Chris Landreth is a deeply moving and visually astonishing documentary animated in 3D about Canadian animator Ryan Larkin. Once a celebrated filmmaker whose work was nominated for an Oscar, Ryan Larkin descended into drugs and alcohol and ended up begging on the streets of Montréal.

In "Ryan", which is based on some 20 hours of actual interview footage, an animated Landreth interviews Larkin in a rundown café populated by freaky characters, one of whom is flattened out on a table. Landreth portrays Ryan Larkin as a disintegrated, incomplete figure, with only parts of his head, hands, arms and body visible. Life has literally gnawed at him. Landreth himself has also received some blows from life but that, as he says in the opening scene, is another story. At one point Landreth, whose emotions show through the hands reaching out from his face towards Ryan, asks the wrong question. Ryan literally explodes, turning into a demon with multicoloured spikes coming out of his face.

Landreth has ingeniously woven into his film two of Larkin's critically acclaimed shorts from the early 70s, images of Larkin's former self, his old girlfriend and his producer. The film is so rich in detail you have to see it more than once.

"In" by Philipp Hirsch is hard to classify and I'm still trying to figure out what it was all about. Hanna has to decide. But about what? A naked girl runs through the woods. Something is hiding underneath the foliage hanging over a mountain stream. Abstract organic shapes that are at once three and two dimensional dissolve when two parts make contact. We are led through a three dimensional system of tunnels populated by one footed creatures. A boy's underpants. The girl is lying on the grass. She looks at the tiny underpants in her hands. We turn inside outside inwards to emerge outside again. And somehow it all makes sense. It is as if the inner contortions of an existential dilemma are visualized. "Hanna. It's about your belly again. Lena or Dave, you have to decide" a male voice says. Who is Lena? Who is Dave? We are left to fill in the blanks, haunted by the eerie and beautiful images Hirsch has created. Maybe this is what thinking and deciding look like. Maybe.

In "Birthday Boy" by Sejong Park a little boy rummages about in what turns out to be the remains of a plane that has crashed into a building. He emerges with a screw and runs down to a railway where he places it on the track. In the distance a train is approaching. It is carrying tanks. It is 1951, the time of the Korean war. When the train has passed the little boy picks up the flattened screw and holds it a distance from another piece of iron. The boy smiles. It's magnetic. He continues his way home, running, hiding and playing soldier on his own. The town looks desolate. There is no one else to play with. When he arrives home he finds a parcel on the doorsteps. He opens it and takes out a medallion on a necklace and an old boot. He puts on the necklace and parades in front of the house, holding a stick against his shoulder as if it were a gun. Then he goes to his room to play with the toy tanks and fighter planes he has made out of the scrap metal he has found on the streets. In the final scene we hear his mother arrive home, cheerfully greeting him, unaware of the news that awaits her.

In less than 10 minutes Sejong Park manages to give a vivid portrayal of the effects of war. The film is largely carried by the storyline and yet if it hadn't been animated it would have had far less impact. The 3D technique employed by Sejong Park allowed him to exaggerate the characteristics of nearly all of the films features, from the boy's innocence to the desolate landscape and the gentleness with which he treats the screw.

Other highlights included the third part of Phil Mulloy's trilogy "Intolerance", this year's Oscar Award winning short "Harvie Krumpet" by Adam Elliot, "The dog who was a cat inside" by Siri Melchior about, well, I think you guessed it, "What Barry Says" by Simon Robson, which employs the language of stencil art and 50s propaganda movies to create a compelling critique of U.S. foreign policy and "Le Portefeuille" by Vincent Bierrewaerts, about a man who finds a wallet and then splits into two persons, one walks past it, the other picks it up, one spends the money, the other tries to return it to its owner.