When was the last time you laughed at a chair? That you thought, now that's a funny chair? Chairs don't really have a reputation for being outrageously funny. At the Droog Design retrospective, currently at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, The Netherlands, there are two chairs that I thought were pretty funny. Both are part of the do create collection of products inspired by the do brand, the brand without a supporting product, thought up by Dutch advertising agency KesselsKramer.

The first chair, designed by Jurgen Bey, at first looks like an ordinary chair, except that one of the legs is shorter than the other three and not just a little bit. Put a few magazines or books underneath and you will have a chair with a built in library. The second chair, designed by Marijn van der Poll, is what you would like to do to one of those Ikea chairs that you have to put together yourself, if it weren't for the fact that you would then have no chair left. It comes as a 100 x 70 x 75 cm box made out of 1.25 mm steel together with a big sledgehammer. The hammer lets you sculpt the box into the shape you want, while allowing you to unleash some of the aggression that has been building up over the course of another day at the office. Or you could do as during the International Furniture Fair in Milan in 2000, when the collection was first presented, and have visitors add a few blows to the box.

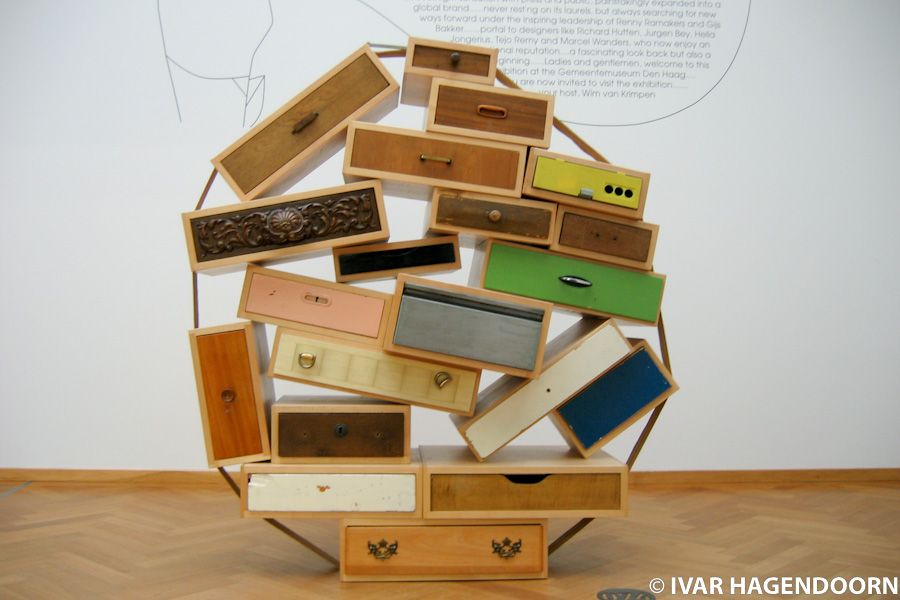

At the exhibition "Simply Droog: 10+1 years of avant-garde design" you can see all of the works that put Droog Design at the forefront of international design. Marcel Wanders' Knotted Chair (1996), Tejo Remy's Chest of drawers (pictured above) and Milk bottle lamp both from 1991, Gijs Bakker's Coffee pot (1997), which has a knitted cover that has been glazed to the pot and Rody Graumans' Chandelier (1993), consisting of 85 light bulbs.

There are also many lesser-known works, such as Matijs Korpershoek's bathroom mirror, which reveals a text when it steams up, Simon Heijdens' numbered sugar cubes (2003), which introduce an element of choice into an otherwise identical product, but one that disappears as the product itself dissolves and Claudia Linders' dress made out of labels contributed by visitors of earlier exhibitions where the project was shown. The names on the labels confirm that most visitors to design fairs and exhibitions wear designer clothes, or at least those who care to join the project. But perhaps Claudia Linders just picked the well-known names to make her point.

The exhibition was designed by Studio Jurgen Bey and consists of a chronological and a thematic part. The thematic part was surprisingly uncharacteristic of Droog Design. In six rooms an area had been delimited by red-white tape, which you were not allowed to enter. These areas were supposed to represent the layout of six typical Dutch rooms, with black tape outlining a bed or a table. Within this virtual environment the various objects were supposed to enter into a dialogue with their equally virtual inhabitants. I think the whole concept was flawed because the objects should enter into a dialogue with the visitors of the exhibition. Now the designs were reduced to museum distance'. Since you could only look at the objects, in the room dedicated to designs around the concept of tactility (pictured above) you were unable to experience what the objects explored.

The chronological part of the exhibition was better conceived. On one side glass displays with magazines and catalogues gave a chronological overview of 10 years of Droog Design, while on the other side objects had just been taken out of their moving boxes. Some of the boxes had been stacked so as to resemble the architecture of the Gemeentemuseum, but that may just be me. It was a bit of a mess, which was good. Whereas the thematic part was a sterile museum display this part seemed more alive.

It was interesting to also visit the concurrent exhibition of Art Deco in the Netherlands on the ground floor of the Gemeentemuseum, the museum's De Stijl collection and its period rooms from the 18th and 19th century, which put the designs by Droog into context.

A beautiful object, or whatever you consider beautiful, usually remains so for some time, although of course you may grow out of it. A functional design such as the Aaron chair by Herman Miller will still be functional after several years of use. But how long does a witty design remain witty? And what is left once you've got the pun, which effectively removes it? This is what I asked myself as I walked through the Droog Design exhibition one more time. I've always been a fan of Droog Design, but seeing 10 + 1 years of Droog Design dampened my enthusiasm somewhat. It's all very clever, but apart from that there's not much to it. Most designs materialize only one idea and once you've got the idea, you just shrug and walk on. And seeing so many clever one-off ideas in one show is as tedious as a collection of aphorisms.

So when it comes to chairs I still prefer functionality and beauty to a good sense of humour. And long legs, of course.

Simply Droog: 10+1 years of Avant-garde Design is at the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, The Netherlands until 13 February 2005.