Penises. There is no escaping them. They are everywhere. Growing out of eye sockets, instead of a nose or just free floating. The American artist Paul McCarthy is clearly obsessed. Give him a piece of paper and a pencil and he starts drawing a penis, with or without scrotum. Occasionally he draws a vagina as well or a mouth enclosing a penis. Sometimes he adds an arrow and a caption "penis" or "paenus" to rub it in.

Rubbing it in is what Paul McCarthy does, and whether with paint, ketchup or chocolate sauce. Excess is the name of his game. McCarthy likes pushing things too far, in his drawings, but most of all in his performances, which always end up as a complete mess.

In "Tokyo Santa" (1996-2004) we see McCarthy dressed up as a mumbling Santa Claus, his beard smeared with chocolate sauce, messing about in his workshop. He still has some drawings to finish. Christmas is around the corner. Damn that can won't open. Where's that knife? He is not wearing any pants. Parents wouldn't like their children to sit on this Santa's lap. Whenever he is done with a drawing he picks it up and wanders across the room looking for an empty spot on the wall. There's a hole in the table. Funny hole. Oops there goes a bottle of ketchup. Oops there goes another one. Where was I. Have to make another drawing. What about a donut? McCarthy bends forward and starts drawing some concentric circles. Dough nut. Do nought. Funny funny word that is.

The video of the performance is projected on four walls, giving some sense of the that is slowly emerging around him. You find yourself looking at this wall, then at that wall. Jammed into the next room are some relics of the performance, a couple of photographs and twenty or so fully decorated Christmas trees. And some bottles of ketchup, of course.

"Tokyo Santa" is part of "Brain Box Dream Box", a Paul McCarthy retrospective at the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven, The Netherlands. Centrepiece of the exhibition is "Piccadilly Circus" (2003), a video installation, which documents a performance McCarthy staged to mark the opening of the London branch of Zürich based gallery Hauser & Wirth. It is also by far the best part of the exhibition.

Before its conversion into a gallery the building used to be bank. When McCarthy visited the space with his gallerist it was still empty and parts of the building still reminded of its former function. He instantly had the idea of doing a piece, rather than just putting up some old work.

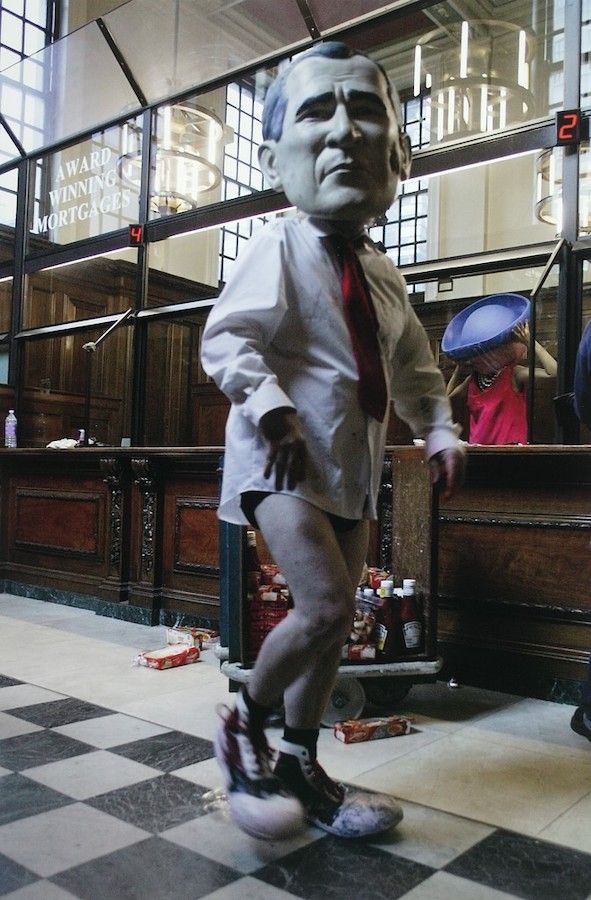

Paul McCarthy, Piccadilly Circus (2003)

"Piccadilly Circus" features George Bush, Osama Bin Laden, the British Queen Mother and two lookalikes, all of whom are easily recognizable by the big rubber masks they are wearing. Osama's turban has the shape of Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim museum in New York. At some point George Bush writes "Guggenheim" on Osama's turban. Just in case. There are some food stains on George Bush's suit. Oh dear, oh dear.

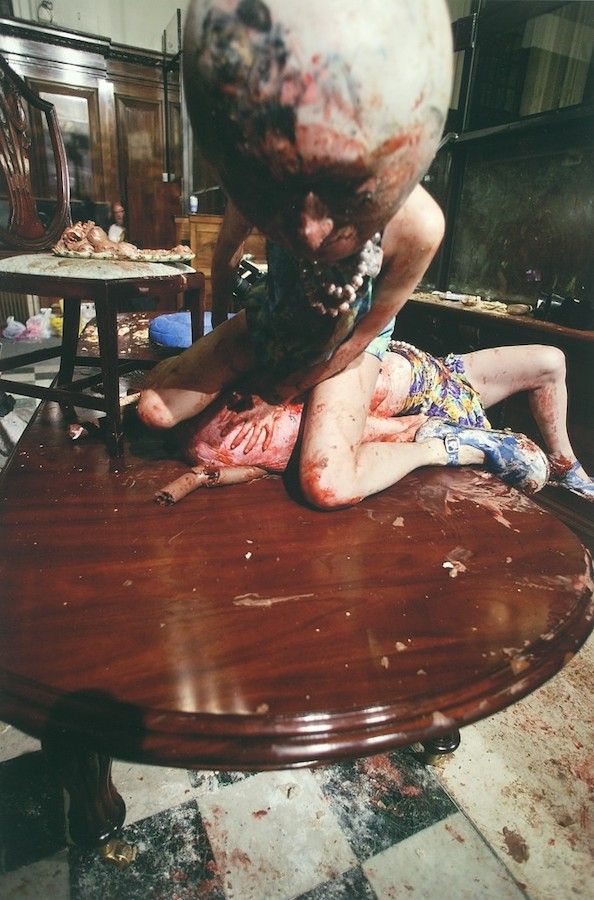

Depending on which moment you enter the installation you can see the three melon headed queenies stumbling on the staircase, bumping into each other and knocking against the doorpost, as they try to make their way into one of the rooms, where George W is making a painting. If you happen to enter an hour or so later you can see them in various states of undress having a go at each other. One of them is stuffing what looks like the tube of a vacuum cleaner up underneath her skirt. Occasionally a mask gets twisted. These things happen. Meanwhile George Bush is having a hard time painting his portrait of Osama bin Laden. His attempt to deposit some cakes and cookies at one of the cashier desks doesn't go as planned either.

It's all downhill from here. I couldn't help thinking of Iraq. Funny, isn't it? George W loses his head while making his way down the stairs to the basement, where he starts drilling some holes. At one point one of his legs is chopped off. Ohh bugger. The queenies are now into body painting. All the while we hear a tape recorder "Cashier number two please... cashier number four please."

The videos are projected on the walls. The room itself has been furnished with what remained when Paul McCarthy had left the building. I would have loved to see the piece at its original location, but if you have a chance do go and see the installation in its present form. This is Paul McCarthy in top shape.

The exhibition at the Van Abbe museum includes many drawings. According to the curator they reveal the artist's thought processes. It's the kind of rhetoric museums use to conceal the fact that they were unable to get hold of some key works for the exhibition. One room consists of three rows of displays containing 96 placemats from a Japanese restaurant, on which McCarthy has scribbled his familiar themes. After glancing at three or four I walked past the others as I moved on to the next room. They appear to be little more than sketches for his performances, installations and sculptures. I don't find Paul McCarthy's sculptures, of Michael Jackson and his monkey, of a head with a penis as a nose, or his inflatable blockhead Pinocchios, all that interesting either.

It is in his performances that McCarthy's ideas and obsessions find their best expression. It is interesting to see the drawings and paintings that he makes in for instance "Tokyo Santa", but outside of the context of their production, they lose much of their appeal. This is what gives them their "aura", to borrow a term from Walter Benjamin, who used it to refer to the objective realm, which gives a work of art its authenticity, the umbilical cord that connects it to its origin.

There's more Walter Benjamin in the work of Paul McCarthy. Art, according to Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproduction, has its roots in ritual. It was only when objects were emancipated from the rituals in which they were embedded that they came to be recognized as works of art. Performance art can be seen as a modern day ritual, to the extent that the collective mythology, which formed the basis of ancient rituals, has now been replaced by a personal mythology. In African tribal art a large penis stands for a fertility symbol, in the work of McCarthy it is referred back to his own private obsessions.

For all the sexual imagery and mutilated body parts there is no real sex or violence in the work of Paul McCarthy, it's all mayonnaise and ketchup. As McCarthy said in an interview he has always been more interested in the simulation of the real. "A mayonnaise jar as an orifice brings into the equation something that the human body cannot - it's about consumption, the act of buying, and fetish."

Paul McCarthy's work is a commentary on the culturalization and conditioning of desire, whereby desire is to be understood not as desire for something that is lacking or for a pleasure that will fulfill it, but in the sense of French philosophers Deleuze and Guattari, as an unlimited, indeterminate, productive process that branches off in all directions before it is codified, channelled, suppressed, re-routed and rendered harmless.

McCarthy breaks down the social codes that confine and direct desire towards socially acceptable goals. It is OK to get drunk, but only during the weekend. It's OK to go crazy, but only in a club or at a party. McCarthy is not a madman, least of all when he dresses up as Santa Claus or some other character. He takes the lid off the pan and reveals what is boiling inside. In "Bossy Burger" (1991) we see a mumbling McCarthy dressed as a chef and wearing a grinning rubber Alfred E. Newman mask turn a kitchen into a complete mess. As in all his performances McCarthy frequently loses all sense of purpose. He begins to wander around the set, fiddling with whatever he finds on his way. It is society that demands that we finish what we started, that we empty our plate before we get dessert.

In the work of Paul McCarthy desire wanders freely and it is no accident that this entails a becoming-child, in the terms of Deleuze and Guattari. Children enjoy messing around with paint. They like to play outside even when it is raining, without worrying about their clothes getting dirty. McCarthy still likes to jump in puddles. Yet he does not seek to awaken the child in us. The child is a construction. In their collaborative video installation "Heidi: Midlife Crisis Trauma Center and Negative Media-Engram Abreaction Release Zone" (1992) Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley deconstruct Johanna Spyri's famous story, which creates a fictional ideal of childhood innocence, in which everything belonging to nature and the country side is associated with health and joy, whereas culture and the city are associated with sickness.

Parents and priests never tell you what to do, only what not to do. Don't play with your food, my mother always told me. And this is exactly what McCarthy does. My mother would have smacked him in the face. In "Piccadilly Circus" the British Queen mother engages in an orgy of sex and food, while George W's behaviour is not exactly presidential either. This is why McCarthy's work is perceived as subversive. Look, they say, this is what happens when you don't control yourself. And they're right. But take another look at the figures in McCarthy's performances and you see what you get when desire is suppressed and channelled in the wrong direction: Religious, political, capitalist and artistic fundamentalism.

Paul McCarthy, Brain Box Dream Box is at the Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands until 25 October 2004.