For a moment I too was deceived. The pinewood in the paintings of the Flemish painter Cornelius Gijsbrechts looks astonishingly real. With its knots and splinters even from up close it looks as if a piece of wood has been varnished.

I was reminded of the famous anecdote from antiquity about the competition between Zeuxis and Parrhasios as to who was the best painter. Zeuxis' painting of a bunch of grapes was so realistic birds tried to eat them. When he asked Parrhasios to remove the curtain so he could see his painting, it turned out that the curtain was actually painted. Zeuxis admitted defeat, saying that he had deceived the birds, but that Parrhasios had deceived him.

Cornelius Gijsbrechts specialised in trompe-l'oeil paintings. Little is known about his life. He is thought to have hailed from Antwerp. His first known paintings, dating back to 1657, are traditional still lifes. As of 1662, however, he began producing trompe-l’oeil still lifes. From 1668 to 1672 he worked at the Danish court, where he produced most of the paintings for which he is now famous. In 1672 he moved to Stockholm, where he lived for several years, and from there he moved on to Germany. That is where the trail ends.

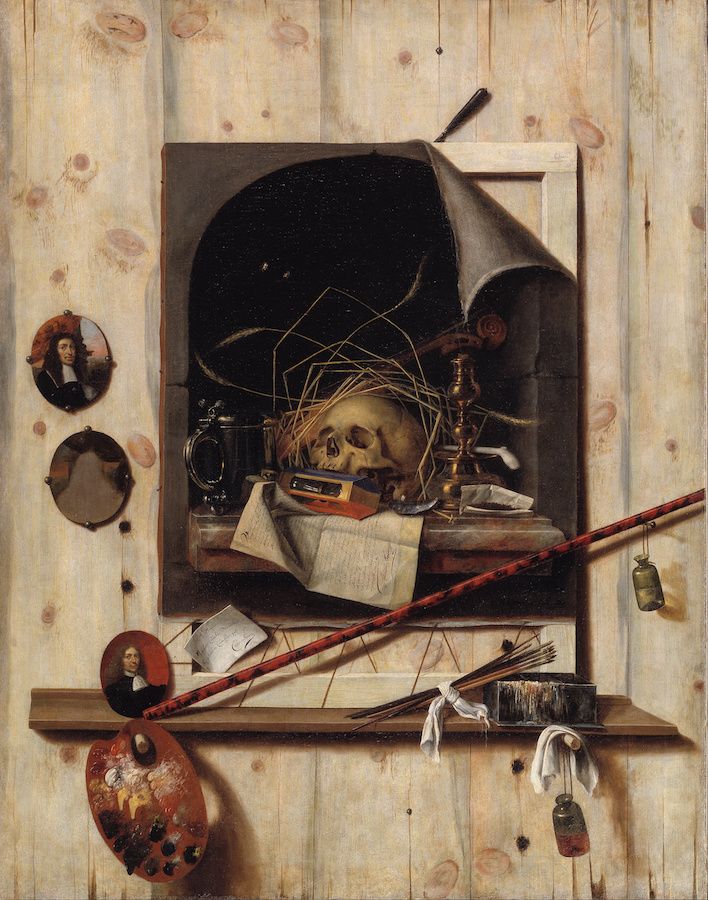

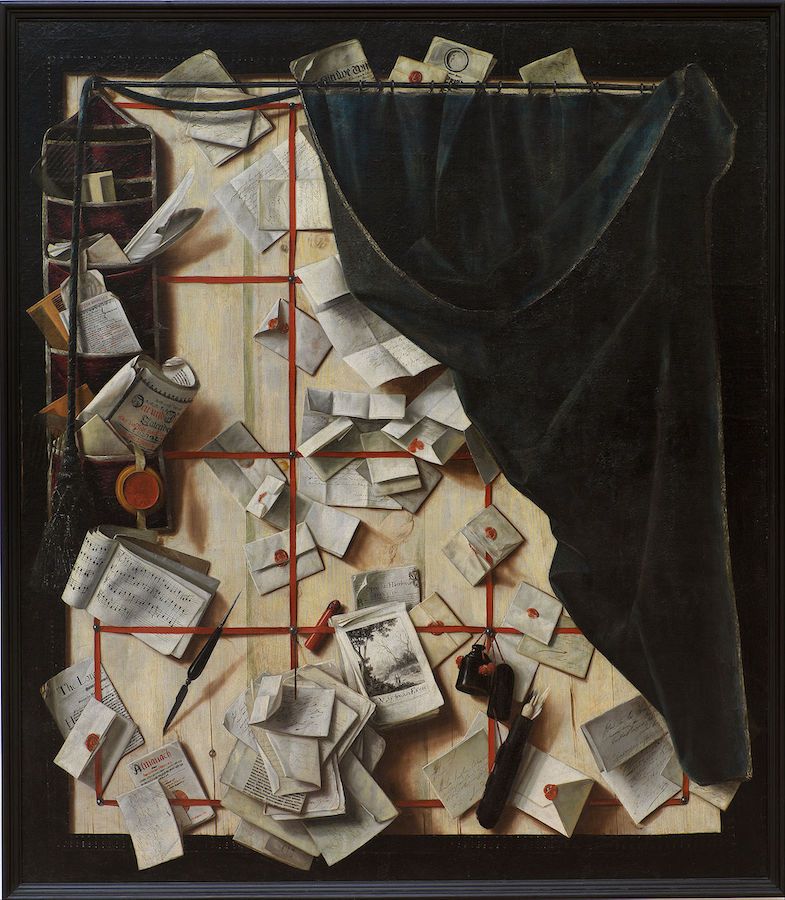

Cornelius Gijsbrechts: Trompe l'oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (1668) (left), Trompe Oeil with Violin Painter Implements Self Portrait (1675) (middle), Board Partition with Letter Rack and Music Book (1668) (right)

Gijsbrechts' most spectacular achievement is a work, which shows an easel, a still life of fruit, the back of a painting resting against the easel, some brushes, a palette, a small portrait of Charles V, King of Denmark, and a written note. The panel as a whole has been cut out along the contours of the scene it depicts, adding to the illusion. To appreciate the illusion it is best seen from a distance.

Another painting, "Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life" (1668), also shows a palette and brushes among other objects. What I find interesting about the palette is that to render it convincingly Gijsbrechts had to DO on the canvas what he did on his actual palette. Aristotle would have cheered at such an example of mimesis.

It is interesting to observe that, insofar as technique is concerned, 17th century painters such as Gijsbrechts already achieved great heights. In the 19th century the American painter John Frederick Peto painted various similar trompe-l'oeil paintings, but except for "The Cup We all Race For" his work does not even begin to compare with Cornelius Gijsbrechts' formidable craftmanship.

Perhaps the most interesting painting in the exhibition is an unframed painting depicting the reverse of a framed painting (pictured above circa 1670-72). To add to the effect, attached to the painting within the painting, Gijsbrechts has painted a piece of paper with the number 36. Gijsbrechts included paintings of the reverse of a painting in various other works, but as an independent work this painting could easily fit into the 20th century avant-gardes.

As a matter of fact Roy Lichtenstein also painted the rear side of a painting in his signature comic book style, "Stretcher Frame with Cross Bars III" (1968). I don't know whether he knew the painting by Gijsbrechts. In any case, Gijsbrechts version is far more striking. There is no mistaking "Stretcher Frame with Cross Bars III" for a painting by Roy Lichtenstein, whereas the painting by Cornelius Gijsbrechts is almost self-effacing.

The Eye Deceived. Painted Illusions by Cornelius Gijsbrechts is at the Mauritshuis, Den Haag until 15 May 2005.