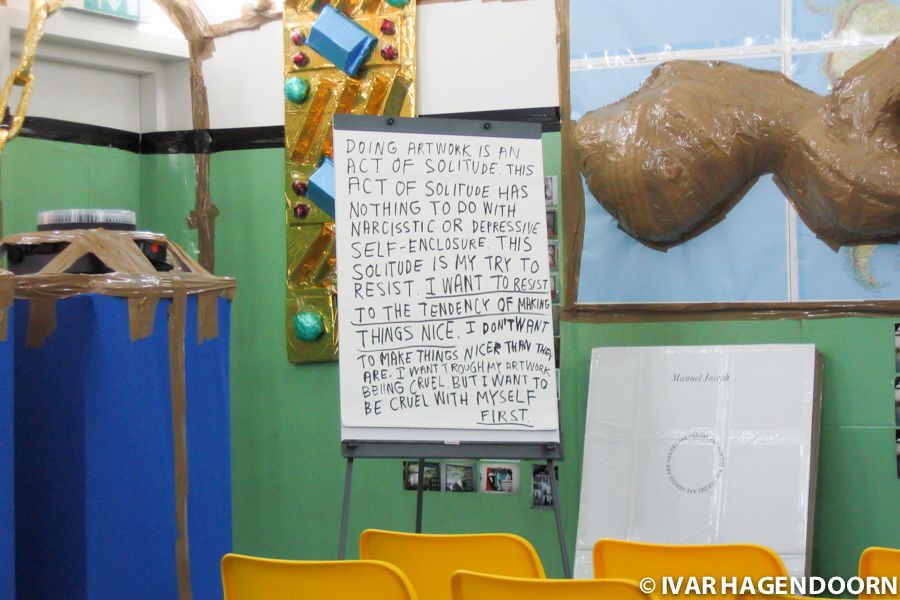

"Energy yes! Quality: No!", or so it says on a banner above the entrance to the Thomas Hirschhorn exhibition at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht, The Netherlands. "I don't make political art. I work politically. Working politically means working without cynicism, without negativity and without self-satisfying criticism", it says on another banner. So there. Thomas Hirschhorn has a lot to say. The walls of the exhibition are filled with banners and enlarged press releases and transcripts of interviews. Easel pads display even more statements: "As an artist I have to stay disobedient. I want to stay unaccommodating. I do not want to be critical. I don't want to polemicize."

Hirschhorn's statements read like a manifesto without an underlying programme. They are a pure manifestation of desire in the sense of Deleuze and Guattari, desire not as a longing for what is absent but as a productive machine, a creative force. A recurring line in his statements is "I want". "I want to work simply and economically. I want my work to be dense and charged. I want to over-work my work. I want to work politically. I want to face up to the World around me, I want to remain attentive and lucid."

"Belief may be no more, in the end, than a source of energy, like a battery which one clips into an idea to make it run," J.M. Coetzee writes in Elizabeth Costello. It is obvious from looking at the work of Thomas Hirschhorn and reading his texts that his battery is fully charged and firmly clipped into his ideas. His work reminds me of the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which exhibits a similar drive and sense of urgency.

There is a lot to see at "Anschool", as the exhibition is called. It is set up as a school with classrooms, reading desks, plastic yellow chairs and desks covered with blue canvas. The floor has been furnished with blue linoleum. When you notice you realize that that is what you smelled. There are maps on the walls with mountain rugs of industrial tape that look like some kind of tumors. Anschool is to school what anarchy is to established order and what the Body without Organs of Deleuze and Guattari is to the organism. As it says in the press release "Anschool rejects analysis, training and the creation of a 'school'. (..) Anschool stands for courage, curiosity and perseverance." I like that. I also like it when Hirschhorn states that he doesn't want to make things nicer and that "better is always less good."

Anschool is at once a project in itself as a retrospective of some of the projects Hirschhorn has realized in the past few years. There's his "Pilatus Transformator" (1997) and "Hotel Democracy" (2003), first exhibited at the Tate Modern, a huge, 15 meter long 2+ meter high doll house, with enlarged news photos as wallpaper. Sleep tight while the world is burning. Hirschhorn has mixed real furniture such as mirrors and table lamps with doll house furniture and children chairs. Something is out of order in the new world order. Every room features an emergency exit, but they don't lead anywhere, they're just illustrations on the wall.

Hirschhorn's displays, he doesn't like the word installation, look like three-dimensional collages. In Anschool fluorescent lights and picture frames have been taped to the walls. Cardboard, plywood and industrial tape are his favourite materials. The empty rolls of tape are not thrown away but included in the exhibit. Hirschhorn is not afraid of self-mockery. One display shows photos of cars with smashed windows and dangling mirrors, which have been temporarily repaired with plastic bags and industrial tape. This is what I like about Thomas Hirschhorn, he is serious, he cares and he is willing to fight for his ideas, but he is not pretentious. Some of his projects are simply hilarious. A video shows Hirschhorn handing out collages at an underground entrance in Paris. A photo series shows the collages he put under the windscreens of cars parked in some Parisian neighbourhood. Another video, filmed from a room on the first or second floor of some apartment block, shows refuge collectors conscientiously dismantling one of his installations.

Hirschhorn's "altars" for Raymond Carver, Piet Mondriaan and Ingeborg Bachmann and his monuments for Spinoza and Deleuze, which he erects at non-descript urban sites are equally multi-layered. They can be seen as mocking the kind of memorials that people put up at places where some personal tragedy has occurred, they question the politics of official monuments, but they are also a real tribute to some of Hirschhorn's intellectual heroes. I like the idea of these altars. I mean, who would put up a Spinoza monument in Amsterdam's red light district? Isn't that just great?

Hirschhorn is a keen and honest observer of his own work. His Deleuze monument in Avignon had to be dismantled because of vandalism and theft, which Hirschhorn attributed to the fact that he couldn't be on site for the entire duration of the project. And so, for his Bataille monument at the Documenta 11 he lived for two months in an apartment at the site.

Thomas Hirschhorn is also well aware of the objections and reservations one might have in relation to his work. It might be argued that an exhibition such as Anschool lacks the immediacy of his public art projects. But as it says on one banner "There is no ideal place for art. Not in the museum, not in the gallery, not in the street, not in the collector's home." And as Hirschhorn wrote of his Bataille monument at Documenta 11: "Work in public space is never a total success and never a total failure." Of course this is also true of work in a museum, where the conditions are always perfect, but where, because of that, you always see the work in the same light, literally.

Anschool looks like a mess, but apart from the burned landscape almost everything is in fact carefully arranged. One can even detect a grid in the displays, on the walls and on the tables. Anarchy is never total. But it doesn't have to be, as long as it shows the potential for change. It is hard to look at the work of Thomas Hirschhorn and not feel infected by his energy. Yes, art does matter. Yes, art can make a difference.

Thomas Hirschhorn: Anschool is at the Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, The Netherlands, until 11 September 2005.