The Centre Pompidou has organized an ambitious exhibition which explores the relationship between dance and the visual arts. A large selection of paintings, sculptures, films, installations and dance works testifies to the ongoing exchange between both disciplines. From Futurism to Bauhaus and from De Stijl to Dada artists have been inspired by dance and the body in motion. Conversely, various choreographers have collaborated with visual artists: Martha Graham with Isamu Noguchi, Merce Cunningham with Robert Rauschenberg, among others and Lucinda Childs with Sol Lewitt. The exhibition brings together works by nearly hundred artists, from Henri Matisse to Matthew Barney and from Vaslav Nijinsky to Trisha Brown.

The exhibition takes its title from an interview with Isadora Duncan, in which she declares that “[her] art is just an effort to express the truth of [her] being in gesture and movement.” “When I was in front of the audiences that flocked to see my performances, I never hesitated. I gave them my soul’s innermost impulses. From the beginning, I have only danced my life” (Isadora Duncan, My Life, 1928). Merce Cunningham has also referred to dance as a visible manifestation of life and other dancers and choreographers have made similar statements. All of this should be read metaphorically or taken with a grain, if not a bucket full, of salt. There is more to life than physical movement.

The exhibition is divided into three sections: the expression of the body, the abstraction of the body and its mechanization and the body as event, each of which is divided into multiple, chronological or thematic, subsections.

The exhibition opens with Henri Matisse’s "La Danse" (1931-33), on loan from the Musée d’art moderne de Paris, not to be confused with the famous version that is in the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. Also included in this section are photos from Nijinksi’s "L’Après-midi d’un faune" (1912), the sculptures that Rodin made of Nijinksi, Matthew Barney dressed up as a faun, a film recording of Mary Wigman’s witch dance and a painting by Emil Nolde of the same.

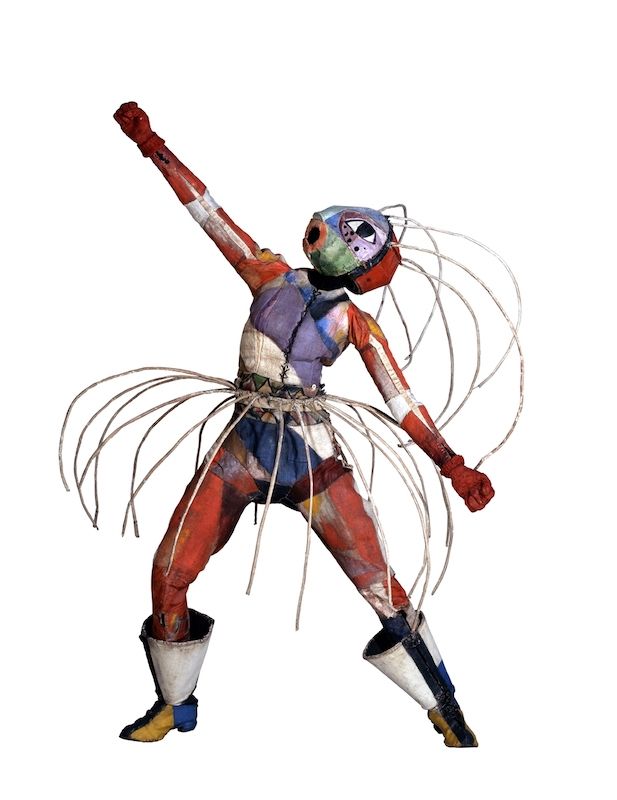

One of the highlights of the exhibition are the sculptures by Lavinia Schulz (1896-1924) and her husband and artistic partner Walter Holdt (1899-1924). The identical year of death is no coincidence: Schulz shot Holdt in the head and then committed suicide. Yes, you read that correctly, she killed him. Schulz and Holdt made these costumes to dance in: they performed under the name "Die Maskentänzer" (The Mask Dancers). Schulz also wrote down a choreographic score for their dances. After their death the costumes and preparatory sketches were put into boxes and stored in the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts where they were rediscovered in the 1980s. The outfits are highly sculptural and reminded me of contemporary creations by fashion designers such as Rei Kawakubo (of Comme des Garçons) and Alexander McQueen.

Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt

The organizers of the exhibition are to be applauded for not concealing the alliance between German modern dance and the Nazi regime. The Nazis labelled much modern art degenerate (“entartet”) and following Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 they actively sought to cleanse Germany of degenerate art through book burnings and by dismissing artists from their teaching positions. They did, however, make an exception for modern dance.

Whereas some dance makers, such as Kurt Jooss, fled Germany after the Nazis took power, others, including Rudolf von Laban and Mary Wigman, not only stayed, but saw an opportunity to further their aesthetic agenda and perhaps they were also captivated by the ideology (*). Dance critics and historians still bend over backwards in their efforts to exonerate Laban and Wigman, claiming that they were coerced or acted out of fear, but the fact is that they and others were committed Nazis. The issue here is not merely that Laban and Wigman erred politically, it is also one of aesthetics (**). Laban’s ensemble choreography fitted perfectly with Nazi ideology as did his goal of promoting a sense of community. In 1934 the Nazis promoted Laban to the position of director of the Deutsche Tanzbühne, which reported directly to Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda. Under the leadership of Laban other German dancers and choreographers quickly fell in line. In 1936 Laban fell from grace when, at a private viewing for Nazi luminaries, Hitler and Goebbels expressed their displeasure at the performance Laban had been assigned to create for the opening night of the 1936 Olympic Games. In 1937 Laban left Germany after he had failed to ingratiate himself with Goebbels. Many others stayed.

The second section of the exhibition looks at the birth of abstract art through the lens of dance and choreography. A video projection shows the abstract figures created by Loïe Fuller’s famous "Serpentine Dance", while works by Sonia Delaunay, "Bal Bullier" (1913) and František Kupka, "La foire ou La contredanse" (1921-22) show how artists’ attempts to capture the body in motion resulted in colourful abstract paintings. I loved Sophie Taeuber-Arp's (1889-1943) abstract paintings, which are a feast for the eye. I didn't know that she was also a dancer. She studied with Laban and danced with both Laban and Wigman and in the 1920s, while in Zürich, she performed at the Cabaret Voltaire.

Dance and visual art come together in Oskar Schlemmer’s (1888-1943) "Triadic Ballet" and in the work of Nicolas Schöffer (1912-1992) whose cybernetic sculptures inspired by the work of Norbert Wiener move in reaction to the environment. In 1956 Maurice Béjart performed a ballet with Schöffer’s "CYSP1". In 1973 Schöffer collaborated with Alwin Nikolais on a project, "KYLDEX1", which still looks futuristic. I must admit that I don’t recall having seen his work before. Schöffer's work deserves to be better known. Fifty years ago he was already wooing audiences with interactive works.

Unfortunately, this section also includes a totally superfluous work by Olafur Eliasson, "Movement microscope", which was created especially for the exhibition and in which dancers intervene in the daily life of Eliasson’s Berlin studio. It is pretty stupid and shows what you can get away with as a contemporary artist once you have made a name for yourself.

The third section, "dance and performance/the body as event", brings together all the usual suspects, from the Cabaret Voltaire to Jackson Pollock and Yves Klein and from Merce Cunningham’s collaborations with Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Nam June Paik, to the work of dancers and artists associated with New York’s Judson Church and the “happenings” of Allan Kaprow. This is also where the exhibition concept begins to unravel. Andy Warhol’s "Dance Diagram" features dance steps that you can actually try out, if you want to, so in that sense it fits into the exhibition, but dance was hardly central to his work.

The exhibition ends with two works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, including his (empty) "Go Go Dancing Platform" (1991), and a recording of "The Show Must Go On" (2001) by Jérôme Bel, which like so many neo-conceptual works from the late 90s and early 00s, now looks terribly dated.

And this brings me to the perhaps rather uncomfortable conclusion and that is that while a large body of work attests to the interaction between dance and the visual arts, most artworks in the show are rather mediocre and not among the artist’s best and most of the dance works are of historical interest only.

Danser sa vie is at the Centre Pompidou, Paris until 2 April 2012. It comes with a catalogue that I didn’t buy, because well, there was not much in the exhibition that warranted spending another EUR 50 on the catalogue. One day I may regret this.

(*) Karina, L. and Kant, M. (2003). Hitler's Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich. New York, NY: Berghahn Books. Originally published as Tanz unterm Hakenkreuz. Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1996.

(**) Kant, M. (2016). German Gymnastics, Modern German Dance, and Nazi Aesthetics. Dance Research Journal 48 (2), 4-25.