I had originally planned to spend a day and a half in Basel, but because the weather was nice I spent an extra day in Zermatt, leaving me with only an evening and a morning in Basel. And so I only had time to visit one museum.

I decided to visit the Kunstmuseum Basel, which for some reason I had skipped when, in 2005, I spent a long weekend in Basel. At the time I only visited the Fondation Beyeler, the Tinguely Museum and the Schaulager. In the meantime the Kunstmuseum Basel has been expanded. It now consists of three venues. The collection of contemporary art is housed in a separate building, a short walk from the two main buildings, thereby exemplifying the thesis put forth by Nathalie Heinich in Le paradigme de l’art contemporain. According to Heinich contemporary art is not so much art that is created now, but an entirely different paradigm.

I was delighted to finally visit an art museum again. The Kunstmuseum Basel has a large and interesting collection of artworks covering the entire period from the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the present. Its collection grew over the centuries thanks to donations from wealthy local merchants, a tradition which continues to this day as showcased by the gifts and acquisitions of the past four years.

Ever since I visited the exhibition Mémoires d’Aveugle (Memories of the Blind) curated by Jacques Derrida at the Louvre I have been fascinated by self-portraits. The Self-Portrait at the Easel (1548) by Catharina van Hemessen is an excellent example of the questions raised by Derrida. The painter painted herself painting herself. Interestingly in the painter portrayed in the painting is not looking at what she is painting, she looks towards a point to the left of the viewer. She is therefore as it were painting blindly. But while painting this self-portrait Catharina van Hemessen had to look at the painting, and not at an image of herself in a mirror. In the act of painting she was thus painting from memory. There is a lot more to be said about this fascinating painting and I now want to reread the entire book by Derrida.

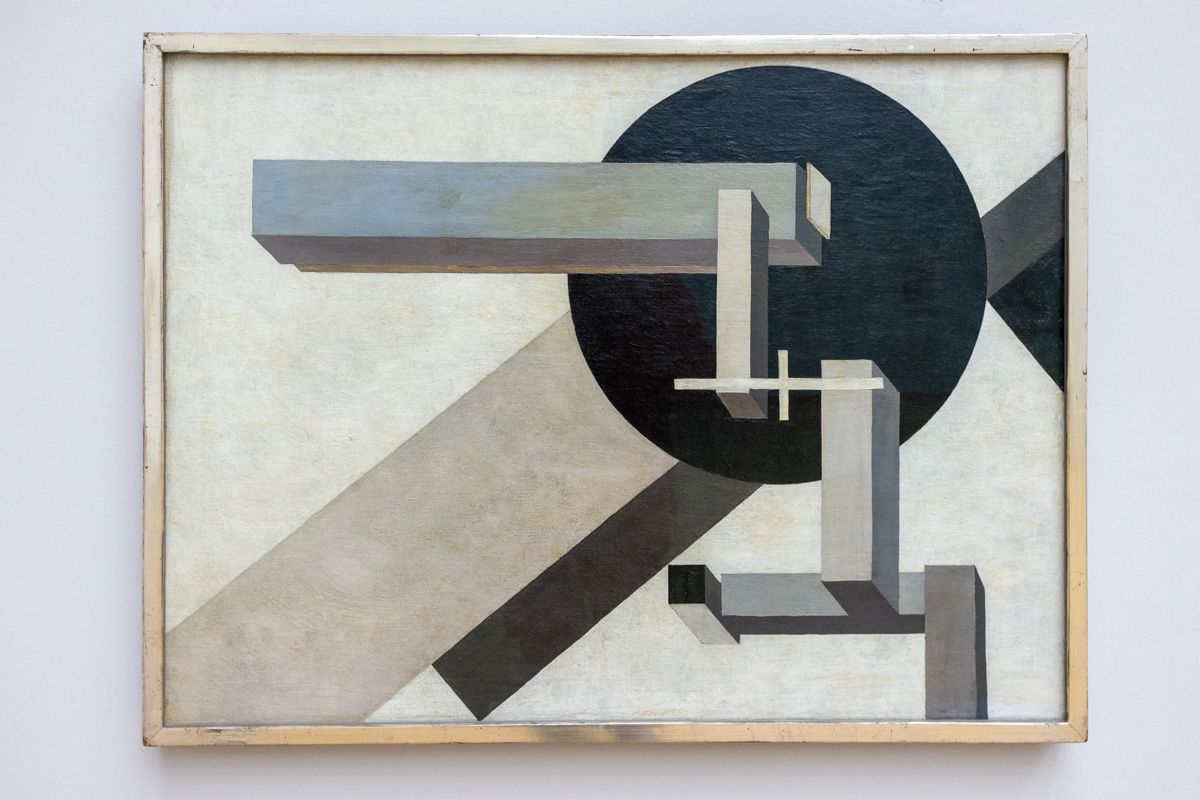

Earlier this year I read a fascinating book about the Russian avant-gardists and so I was pleased to see some works by El Lissitzky and other early 20th century classical modernists. As Sjeng Scheijen argues in The Avant-Gardists, El Lissitzky was one of the first abstract artists who didn't develop abstract painting himself, like Mondriaan, Kandinsky and Malevich, but who adopted it as a student. His work thus shows that abstract art was not an end point or a degree-zero of painting, as the famous black square by Malevich is sometimes taken to symbolize, but instead marked a new beginning, offering opportunities for taking art into new directions.

I love the spatial composition in the work of El Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy and Jean Dubuffet (below). These works set my mind into motion, but in an entirely different way than Renaissance and 19th century paintings.

Works by El Lissitzky (left), Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (middle) and Jean Dubuffet (right)

After seeing so many fascinating artworks I was a bit underwhelmed by the Isa Genzken retrospective at the contemporary art venue.