The exhibition "Les Choses. Une Histoire de la Nature Morte" (Things. A History of the Still Life) at the Louvre is a monumental and magnificent survey of the way artists have represented things from antiquity to the present day. It includes mosaics from ancient Rome and excerpts from movies by Jacques Tati and Michelangelo Antonioni and much, much more, with works by artists ranging from Chardin, Courbet and Cézanne to Duchamp, Broodthaers and Arman. The exhibition is also more than a history of the still life. It aims to show that the many ways in which artists have represented things, from sacred things to the most common things, reveal the ways of thinking, the desires, preoccupations and obsessions of those who depicted them and of the society to which they belonged.

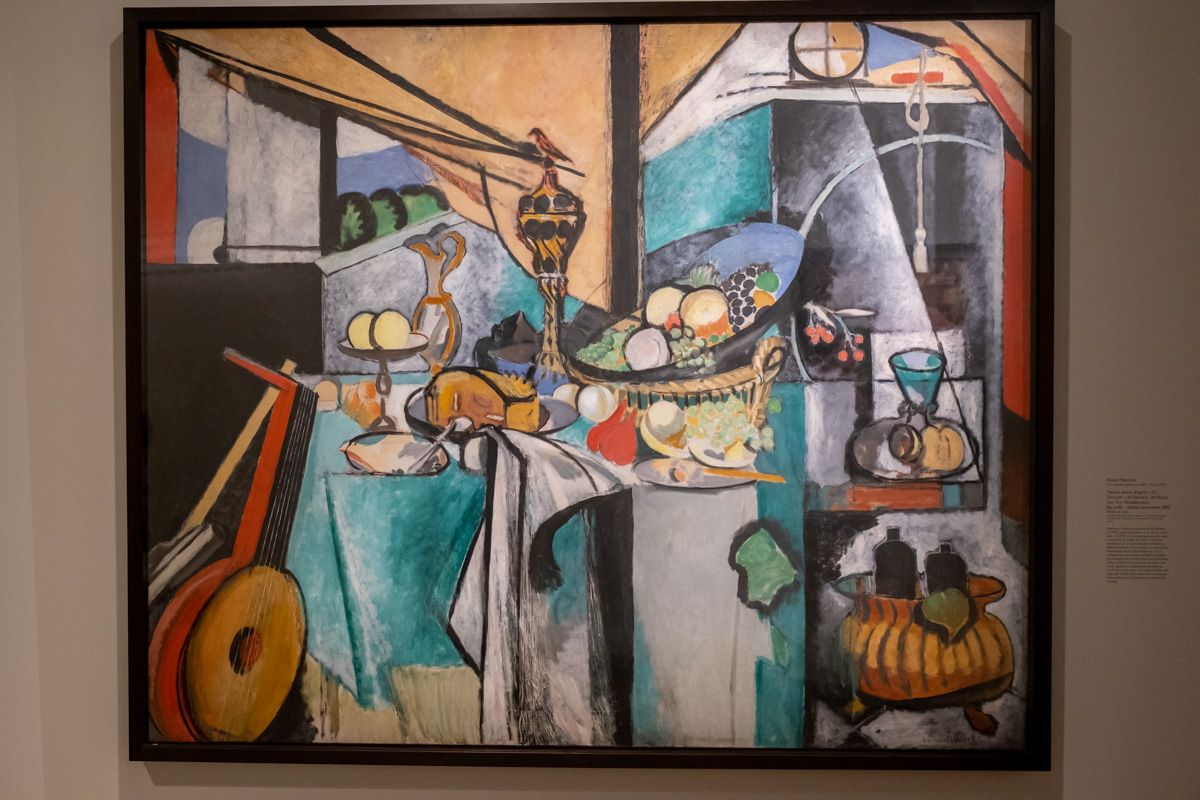

Since the Louvre itself regularly loans artworks from its extensive collection to other museums it is able to loan artworks in return. In total Les Choses includes loans from some 70 other institutions. And so it is that you can see Matisse’s "Still Life after Jan Davidsz. de Heem's 'La Desserte'" (1915) from New York’s MoMA next to the original painting by Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1640) from the Louvre’s own collection.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem (left) and Henri Matisse (right)

There are many more gems, such as "La Table de cuisine" (1888-90) by Paul Cézanne, "Nature mort aux oranges" (1912) by Henri Matisse and a fascinating painting by Jacques Linard, "Les Cinq Sens et les Quatre Éléments" (1627), which combines the formal elements of the breakfast piece, the vanitas and the flower still life. I was also unaware that Manet’s "Bundle of Asparagus" (1880), on loan from the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, is almost a copy of "Still Life with Asparagus" (1697) by Adriaen Coorte, on loan from the Rijksmuseum. The exhibition also includes some great examples of trompe l’oeil paintings that were popular during the 17th and 18th century.

The main trajectory is chronological, but the exhibition plays with juxtapositions, contrasts and similarities between artists, artworks and across time. I also loved the juxtaposition of two paintings by Arcimboldo with a photo by Joel Peter Witkin and Jan Svankmajer’s animated classic Dimensions of Dialogue (1982).

In a similar vein one room juxtaposes Rembrandt’s famous painting of a slaughtered ox (1655) with Francisco de Zurbarán’s equally famous "Agnus Dei" (1635-40), a painting of a dead lamb, with a photo by Andres Serrano of a slaughtered cow’s head on a pedestal. What is distinctively contemporary about the work by Serrano is the eye of the dead cow which looks straight at the viewer.

Another room explores the vanitas paintings, exemplified by two amazing paintings by Franciscus Gijsbrechts and Sébastien Bonnecroy, which remind the viewer of his/her own finitude and the vanity of worldly pleasures through the display of a skull, musical instruments, books, wine and other objects. Also show in this section is a still life of a fruit bowl by Balthasar van der Ast, which is juxtaposed with a video by Sam Taylor-Wood ("Still Life", 2001) that shows the speeded-up decay of a plate of fruit.

There is much to enjoy and to discover at Les Choses. In the late 18th and early 19th century various artists combined the tradition of the landscape painting and the still life, by putting a still life in the foreground with a landscape in the background, resulting in the somewhat odd "Still Life with Watermelons and Apples in a Landscape" (1771) by Luis Egidio Meléndez and the almost surrealist "Nature morte au homard" (1827) by Eugène Delacroix.

In a memento mori and vanitas painting every object is endowed with meaning. With the advent of modernism artists took to painting the thing as just another thing. This can be seen in Manet’s paintings of an asparagus and a lemon and in the work of contemporary artists who invite the viewer to just look at a thing as the thing that it is.

This modernist view finds its literary equivalent in the work of Alberto Caeiro/Fernando Pessoa, quoted on one of the walls, “Things have no meaning: they exist” (The Keeper of Sheep XXXIX). For as he writes in The Keeper of Sheep XXIV:

“The main thing is knowing how to see,

To know how to see without thinking,

To know how to see when you see,

And not think when you see

Or see when you think.”

"Les Choses. Une Histoire de la Nature Morte" is a vast and exhilarating exhibition. It is an invitation to look anew at artistic representations of things and at things themselves. My only criticism is that it is almost too big: the artworks are hung quite close together and the rooms are too small for the number of visitors. I arrived at around 9:30. By the time I left at around noon it was almost too crowded. So if you’re planning to visit the exhibition go early in the morning or late in the afternoon or evening. Another word of advice: it’s best to book a ticket in advance and arrive well before your scheduled time slot. There are long queues at the entrance for the security check.

Les Choses. Une Histoire de la Nature Morte is at the Louvre, Paris until 23 January 2023.