The American-Swiss artist Christian Marclay is best known for "The Clock" (2010), one of the seminal artworks of the 21st century. It is a 24-hour film, which consists entirely of 1-minute long film and television clips, 12,000 in total, each of which showing a minute of the day, on a clock, an alarm clock or a watch worn by a character in the movie from which the clip is taken. The clips are synchronized to the time of the day, thus creating a functioning timepiece. "The Clock" is not only a visual work, showing what people do in movies at different times of the day, but also a musical work, as clocks tick and alarm clocks go off. It has been exhibited around the world and in 2011 it was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice biennale.

I was delighted when I learned that the Centre Pompidou would present a major retrospective of the work of Christian Marclay. Perhaps because Marclay himself or the show’s organizers, didn’t wanted it to overshadow his other work, "The Clock" is not included in the exhibition. There is, however, much to enjoy at this vibrant exhibition and Christian Marclay deserves to be wider known and not just for "The Clock", but for his entire body of work.

Christian Marclay was born in California in 1955 but grew up in Switzerland where he attended the École Supérieure d’Art Visuel in Geneva. He continued his education at the Massachusetts College of Art and the Cooper Union in New York. Inspired by the work of John Cage and Neo-Dadaist and Fluxus artists such as Nam June Paik, he began to create sound collages with the use of gramophone records and turntables. He also founded two bands and once performed in the same program as Sonic Youth and Swans.

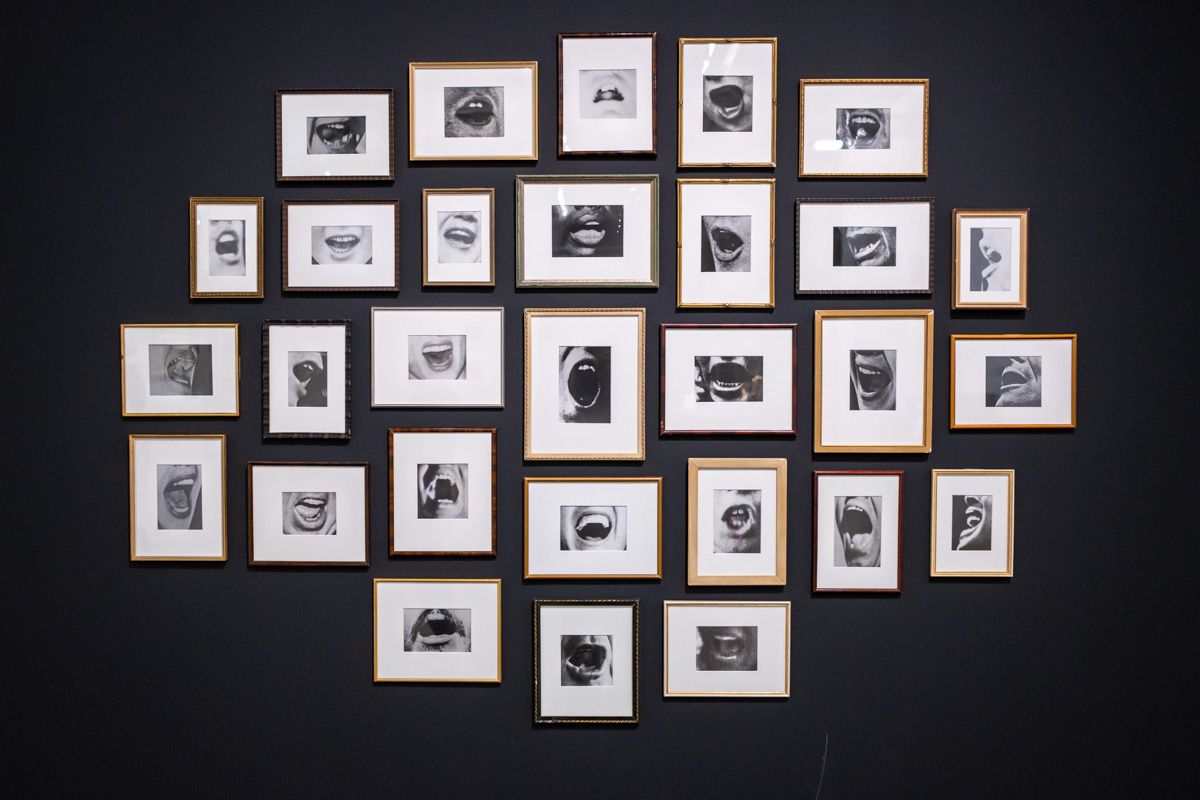

Christian Marclay: Chorus II (1988) (left) and Sound Holes (2007) (right)

Throughout his career Marclay has explored the links between sound and the visual arts, engaging in a number of practices from performance to painting, video and installation. He created installations and collages out of vinyl records and record sleeves. An early photo collage, “Chorus II” (1988), consists of close-ups of, presumably, singing mouths. "Sound Holes" (2007), another work, which I liked a lot, consists of a series of photos of intercoms. It had never occurred to me that there is so much variation in their design.

Another constant in Marclay’s work is his fascination with comic books. In his paintings, drawings and collages, that are reminiscent of both pop art and abstract expressionism, Marclay often appropriates onomatopoeias taken from comic books, “BOOM”, “SNAP”, “THWAK”, “VROOM”, “BANG!!”.

I didn’t think much of some of his conceptual sculptures, though, a nightmare flute that has been almost entirely perforated, a guitar with a drooping neck, an extended accordion, a drum kit set at meters high stems. Like so much conceptual art I look at it and think, ahh, clever, funny, but that is it.

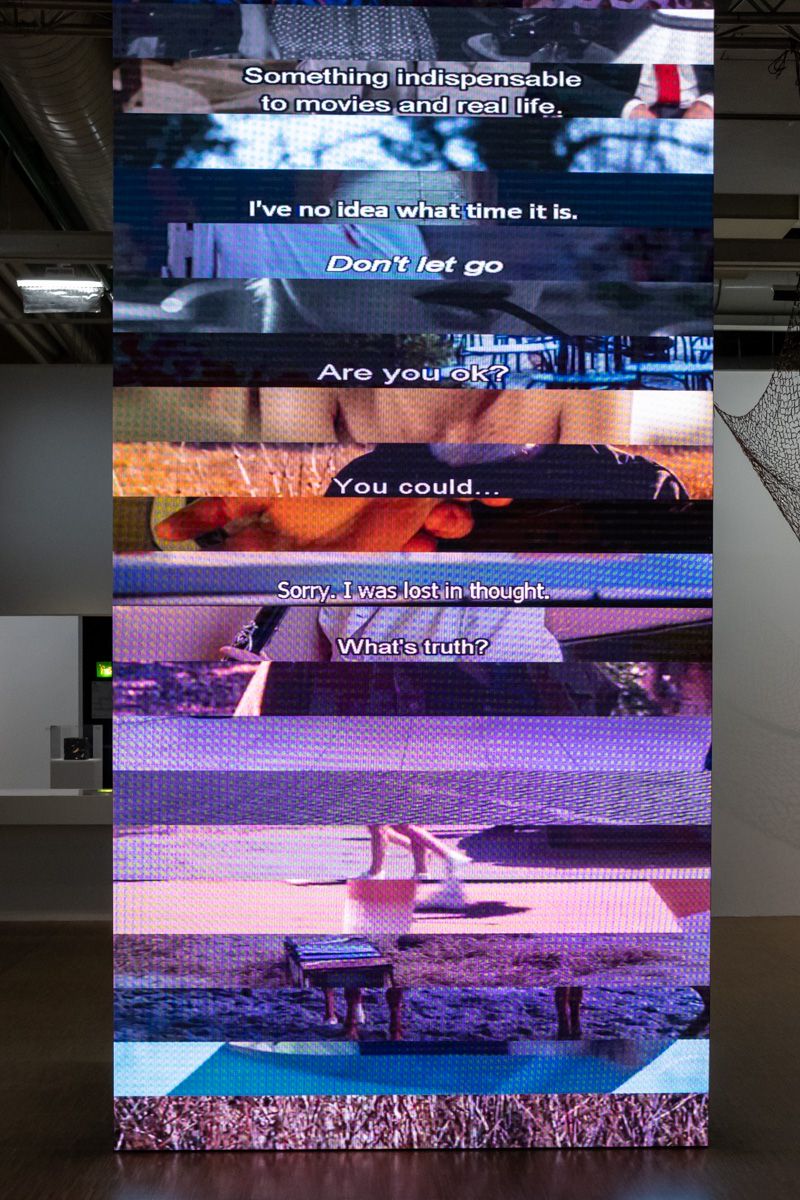

It is in his video works that Marclay’s intelligence shines. “All Together” (2018) samples hundreds of Snapchats. “Subtitled” (2019) consists of a stack of subtitle strips, interspersed with image excerpts. "Telephones" (1995), which can be seen as a study for "The Clock", is an eight-minute montage consisting of movie clips in which the phone rings and someone dials, picks up, hangs up or smashes down the receiver. It is funny and nostalgic, with its rotary dials, phone booths and the scrambling for change. "Doors" (2022), which has its premiere at the exhibition, is composed out of movie clips in which a character opens, closes or passes through a door. These works reveal the conventions of cinema, but they also show that human communication itself is to a large extent conventional. This, incidentally, is the reason for the success of large language models like ChatGPT. They exploit the fact that texts, conversations and so on, frequently use the same turns of phrase.

Christian Marclay is on view at the Centre Pompidou until 27 February 2023. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue available in both French and English.

Christian Marclay, Subtitled (2019)