The exhibition "Futurism and Europe: The Aesthetics of a New World" at the Kröller-Müller Museum explores the relationship between Futurism and other European avant-gardes such as the Bauhaus, De Stijl, Constructivism, Esprit Nouveau and Cubism. It was a joy to see a selection of works by Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini alongside works by Vladimir Tatlin, Sonia Delaunay, Oskar Schlemmer, Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier to name but a few.

Futurism was officially launched on 20 February 1909 when the Italian poet and writer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published his “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” in the French newspaper Le Figaro. It would be followed by a number of other manifestos on, among other things, painting, literature, cinema, dance and cooking.

There is more to Futurism than attempts to render movement in painting, as in Giacomo Balla’s "Swifts Flight" (1913), which opens the exhibition, and his "Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash" (1912). Futurism was not limited to painting and sculpture either. The Futurists embraced architecture, graphic design, fashion, theatre, cinema, advertising and product design. Indeed they sought a complete “reconstruction of the universe” as they proclaimed in the manifesto of the same title. In their view art had to free itself from the limits of traditional art and extend to the whole of life to transform it into a total work of art.

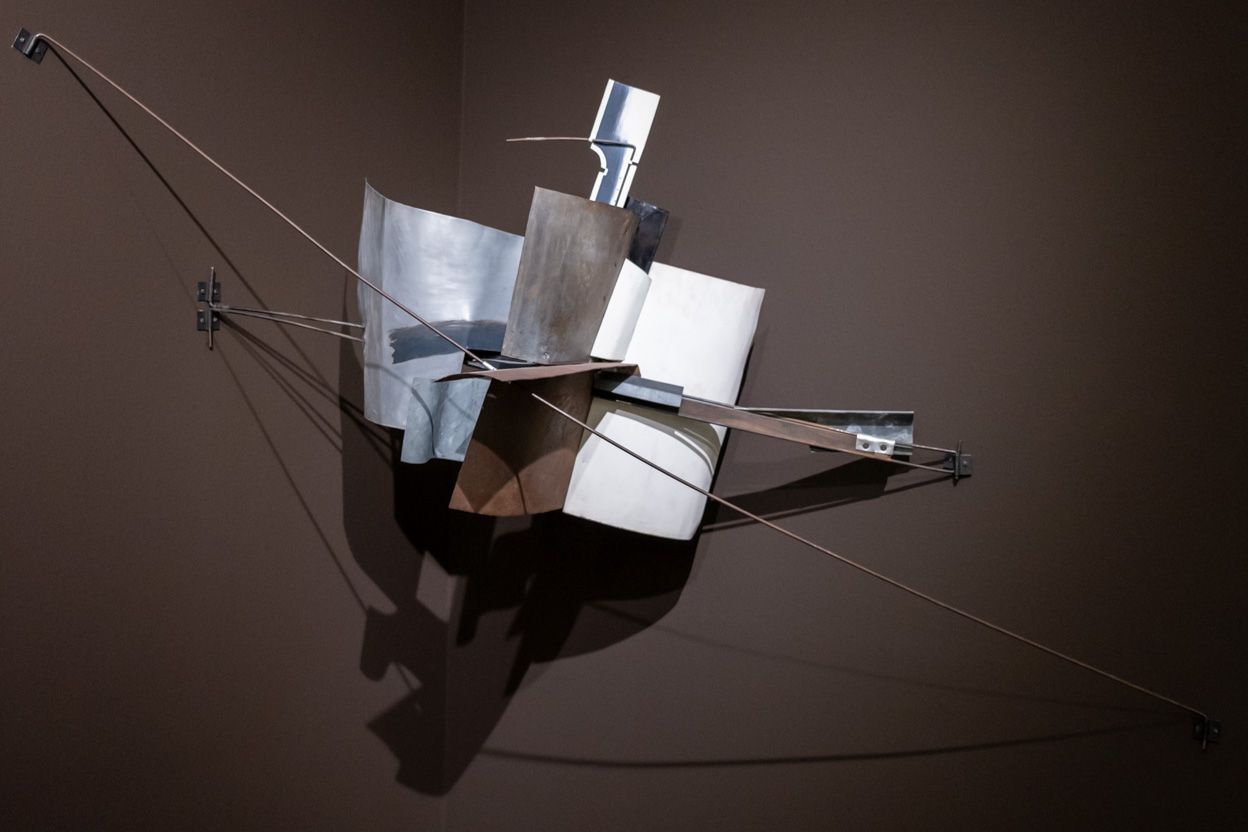

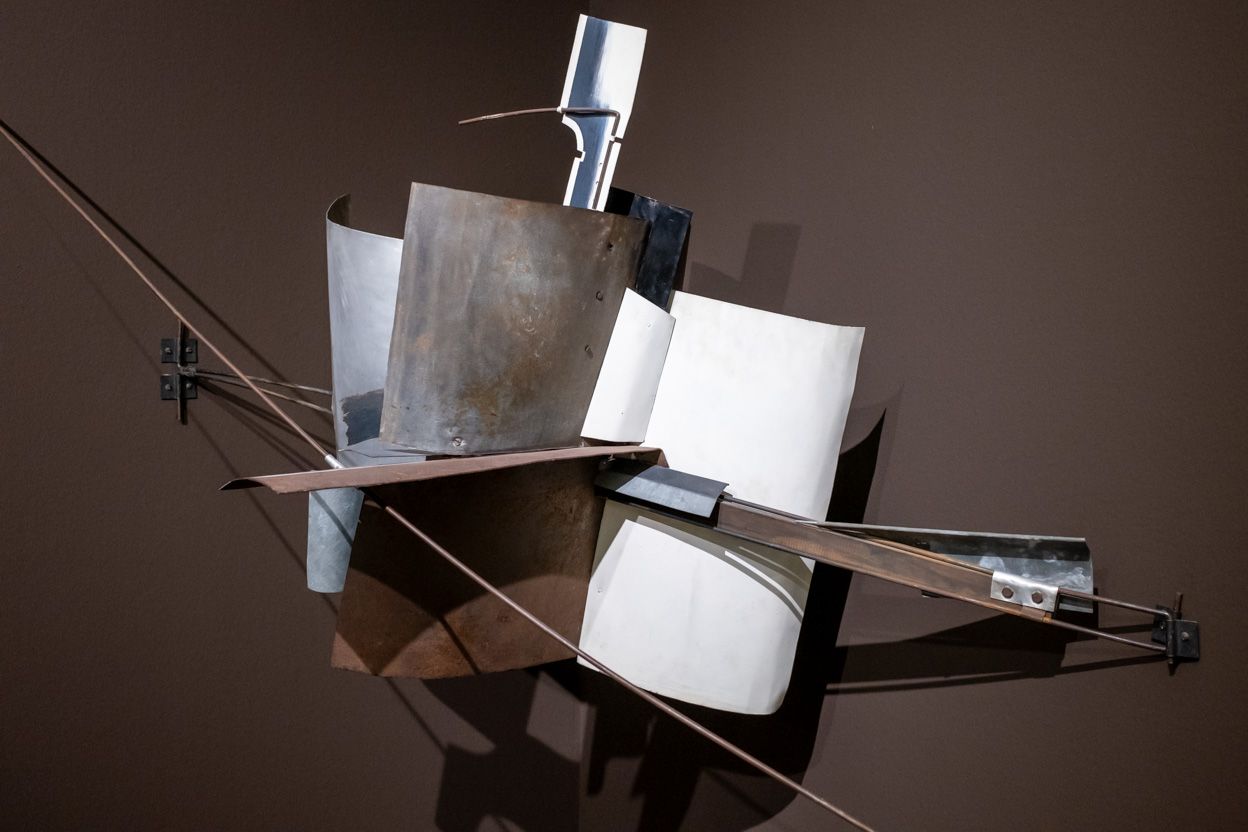

The Futurist sculpture manifesto, written by Umberto Boccioni, aimed to free sculpture from its traditional materials, such as marble or bronze, by resorting to “non-artistic” materials. The exhibition includes some fine examples of sculptures by Futurists and Constructivists including an amazing structure by Vladimir Tatlin. It is somewhat amusing that László Moholy-Nagy intended his "Licht-Raum-Modulator" (1922-30), a moving, light-emitting sculpture, not only as an artwork but also as a device to train the senses and familiarize people with the abundant stimuli of the modern city (light, movement and sound).

Vladimir Tatlin, Complex Corner Relief (1915) (Reconstruction, 1980)

The exhibition also attests to the fascination of the Futurists and other Avant-Garde artists with machines, factories, skyscrapers, cars and the hustle and bustle of the modern city. I enjoyed watching excerpts from "Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt" (Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis, 1927), "Metropolis" (1927), "Man with a Movie Camera" (1929) and "The Bridge" (1928) by Joris Ivens.

The exhibition includes a generous selection of works for theatre and dance from stage design to costumes by Fortunato Depero, Picasso, Oskar Schlemmer and others. Some of these works still look fresh and radical.

The legacy of futurism is still tainted by its association with fascism. Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party in early 1918, which was absorbed into Mussolini's Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919, which in turn would be reorganized into the National Fascist Party in 1921. Marinetti would later withdraw from active politics, but he supported Italian fascism until his death in 1944. Because of their association with fascism the Italian futurists benefited from considerable freedom of expression when the fascists took power, but they refrained from outright propaganda for the regime.

There is much to see and enjoy at "Futurism & Europe: The Aesthetics of a New World". I just wish it had been twice as large and included more works by the Futurists themselves. Had the exhibition been organized by the Centre Pompidou it would have been a major international event.

The exhibition is accompanied by a lushly illustrated catalogue featuring some twenty scholarly essays.

Futurism and Europe: The Aesthetics of a New World is at the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands until 3 September 2023.