Le Paris de la Modernité (1905-1925) is a sprawling exhibition, which brings to life a period when Paris was the cultural capital of the world. Through nearly four hundred works across all artistic domains, from painting and sculpture to dance, cinema, architecture, music, fashion, literature and industrial design, the exhibition celebrates the effervescence of the years 1905 to 1925.

“Le Paris de la Modernité” is the third and final installment in a trilogy of exhibitions at the Petit Palais. I now regret that I missed the first two shows, “Paris 1900: La ville spectacle” and “Paris romantique (1815-1848)”. I always enjoy these kind of exhibitions, as they offer a fascinating glimpse into the diverse artistic landscapes of the past. By showcasing a range of works from various creative disciplines, they allow one to appreciate the developments and innovations that were taking place across different mediums and genres.

There is much to see and enjoy at “Le Paris de la Modernité”, too much almost, with works by Matisse, Picasso, Duchamp, Les Ballets Russes, Sonia Delaunay, Tamara de Lempicka, Cartier, Lanvin and a lot more else besides. It is the kind of exhibition that could only have been organized in Paris. The curators must have raided every museum in France. It even includes a Peugeot Bébé from 1913, on loan from the Musée national de l’Automobile in Mulhouse, and a plane, a Deperdussin Type B from 1911, on loan from Le Bourget Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace.

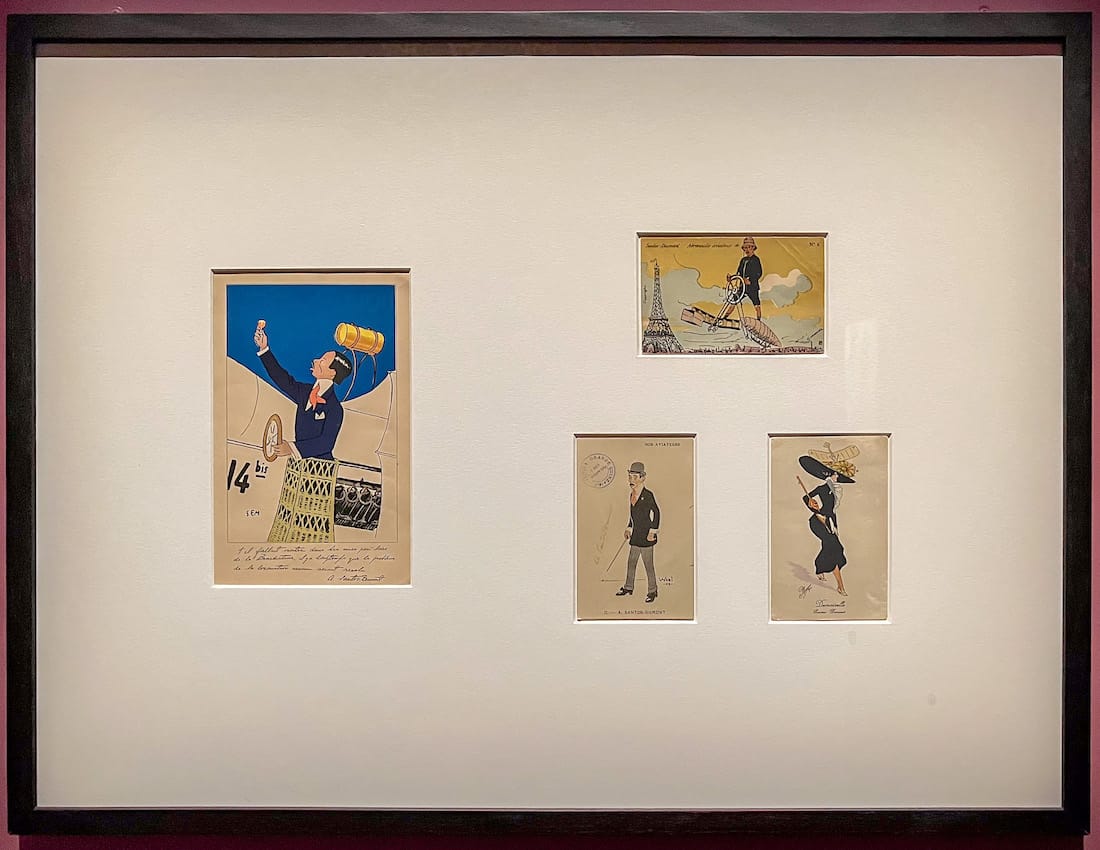

Aviation captured the imagination

In 1901, the Grand Palais organized the first International Automobile, Bicycle and Sports exhibition, which captured the imagination of artists and the general public alike and drew hundreds of thousands of visitors. The exhibition would be held every following year, except in 1909 and 1911, until the start of the First World War. In 1908 part of the fair was dedicated to airplanes and balloons. It proved to be a considerable success and the next year a special aviation fair was inaugurated.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is “La danse du pan-pan au Monico” (1909-11) by Gino Severini, which Apollinaire hailed as “the most important work painted by a Futurist brush”. It is a riot of colour. The painting depicts two dancers, dressed in red, surrounded by a crowd. The figures are composed out of colourful diffracted shapes. The scene appears as if seen through a kaleidoscope and perfectly captures the liveliness and excitement of a party.

Cultural life in Paris came to an abrupt halt in the summer of 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. For several months the city was at the front line. During this time the city was bombed by German Zeppelin airships and German planes. Daily life gradually resumed in late 1915. Theatres reopened and for many artists life went on. Indeed, for some it was a period of heightened creativity. Marcel Proust continued work on the second volume of “À la recherche du temps perdu”. In 1916, Picasso, who as a citizen of neutral Spain was not mobilized, unveiled “Les démoiselles d’Avignon”. In 1917, “Parade”, a ballet performed by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes with choreography by Leonide Massine, music by Erik Satie, costumes and sets designed by Pablo Picasso and a scenario by Jean Cocteau, premiered at the Théatre du Châtelet.

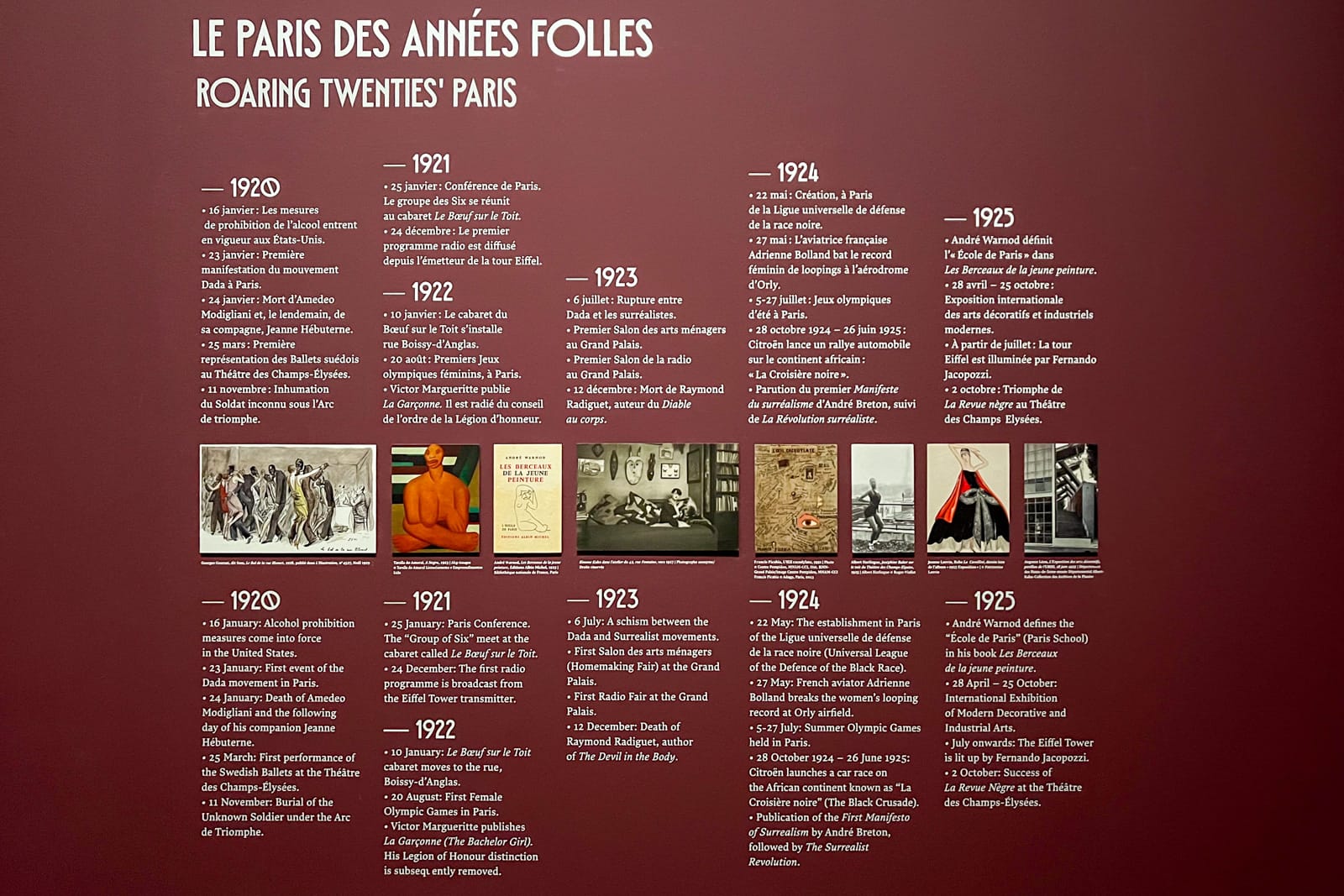

The First World War was followed by the period known as the “Années folles” (crazy years) in France and as the “Roaring Twenties” or the Jazz Age in the United States. It was characterized by a great thirst for life, which was perhaps most evident in fashion, music and design. The period also saw the emergence of a new, emancipated woman, symbolized by an androgynous silhouette and a short haircut. It was around this time that Chanel and Lanvin rose to fame. The exhibition features a selection of costume designs from the period, along with a variety of paintings, drawings, and photographs that highlight the rich exchange of ideas and inspiration between the arts.

In 1926, Josephine Baker, an African American singer, dancer and all-round entertainer, caused a sensation at the Folies Bergère, when she performed wearing a costume consisting of a string of artificial bananas. The dance was set to a Charleston, which became all the rage in Paris. I enjoyed seeing an excerpt from one of her shows as well as the artworks and posters that she inspired.

The second half of the 1920s saw the emergence of Art Deco, of which I’m not a big fan. Even so I enjoyed seeing a generous selection of works from various disciplines illustrating the style.

And with that the exhibition comes to an end. It also marks the end of an era. Paris would continue to attract writers and artists from all over the world and it would remain the centre of intellectual life in France, but its place as the cultural capital of the world was over.

Le Paris de la Modernité (1905-1925) is at the Petit Palais, Paris until 14 April 2024.