The Nicolas de Staël retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris is a revelation. While I had previously had the opportunity to admire some of his paintings in the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou and several other museums, this was the first time that I encountered a comprehensive survey of his work, allowing me to appreciate the full breadth and depth of his oeuvre. I instantly recognized a kindred spirit. Many of his paintings can be described as abstract landscapes: they border between abstract and figurative. They resemble what I do or try to do in some of my photos or indeed in my choreographic work. But of course, whereas in my photos I merely register what I see, in his paintings Nicolas de Staël turned what he saw into art.

I only knew some of Nicolas de Staël’s paintings and was unfamiliar with the myths surrounding his person and his short, turbulent and tragic life. Nicolas de Staël was born in 1914 in St. Petersburg. When he was three years old his family was forced to flee Russia following the Russian revolution. His parents died shortly afterwards and Nicolas and his older sister Marina were sent to Brussels where they were raised by a Russian family. Against the wish of his stepfather Nicolas de Staël went on to study at the Brussels Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts and at the Académie de St Gilles.

In the 1930s de Staël travelled through Europe and North Africa. While in Morocco he met the artist Jeannine Guillou, who had been travelling with her husband and child. De Staël persuaded her to leave her husband and together with her child they returned to Europe, eventually settling in Paris. In 1939 he joined the French Foreign Legion. Two years later, after being demobilized, he returned to Nice, where he lived for three years. During this time he painted feverishly, but dissatisfied with the result he destroyed much of his work. In 1942, Nicolas de Staël and Jeannine’s daughter Anne was born. Around this time de Staël began to paint more abstract works. In 1943 the couple moved back to Paris. Life during the war was difficult and they lived in great poverty.

Towards the end of the war Nicolas de Staël had his first one-man gallery shows. His work was also included in various group exhibitions. Sadly, success came too late and in 1946 Jeannine died from malnutrition and the complications brought on by a therapeutic abortion. Shortly after de Staël met Françoise Chapouton, whom he would marry and with whom he would have three children.

In the early 1950s de Staël’s career took off and he enjoyed considerable success in the United States. In 1953 he signed with the influential gallery of Paul Rosenberg, who encouraged him to create more work to meet the demand of American collectors. In that same year he relocated to the Provence, where, in March 1955, at the age of 41, suffering from exhaustion and depression, de Staël committed suicide.

So much for the story of Nicolas de Staël’s life none of which I knew before visiting the show. I’m only including it here because it probably goes to explain why the exhibition is hugely popular. Indeed, I was lucky to even obtain a ticket. It is as if Paris welcomes back a lost child.

The exhibition brings together more than 200 paintings, drawings and notebooks, many of which are in private collections and are here displayed for the first time. It follows de Staël’s career in chronological order, from his paintings from the late 1940s, which show the influence of Georges Braque, whom he had befriended during the war, through his exuberant abstract landscapes of the early 1950s to his return to more figurative paintings in the mid-1950s. It is quite staggering to see how his work developed in less than ten years.

The exhibition opens with a room which documents the years from 1934 to 1947. It is followed by a room with the paintings De Staël created in 1948-49 in his studio in the Rue Gauguet in Paris, including the wonderful “Eau-de-vie” (1948), which seems saturated with a dazzling energy. The next two rooms, aptly called “Condensation” and “Fragmentation”, show works created in 1950 and 1951.

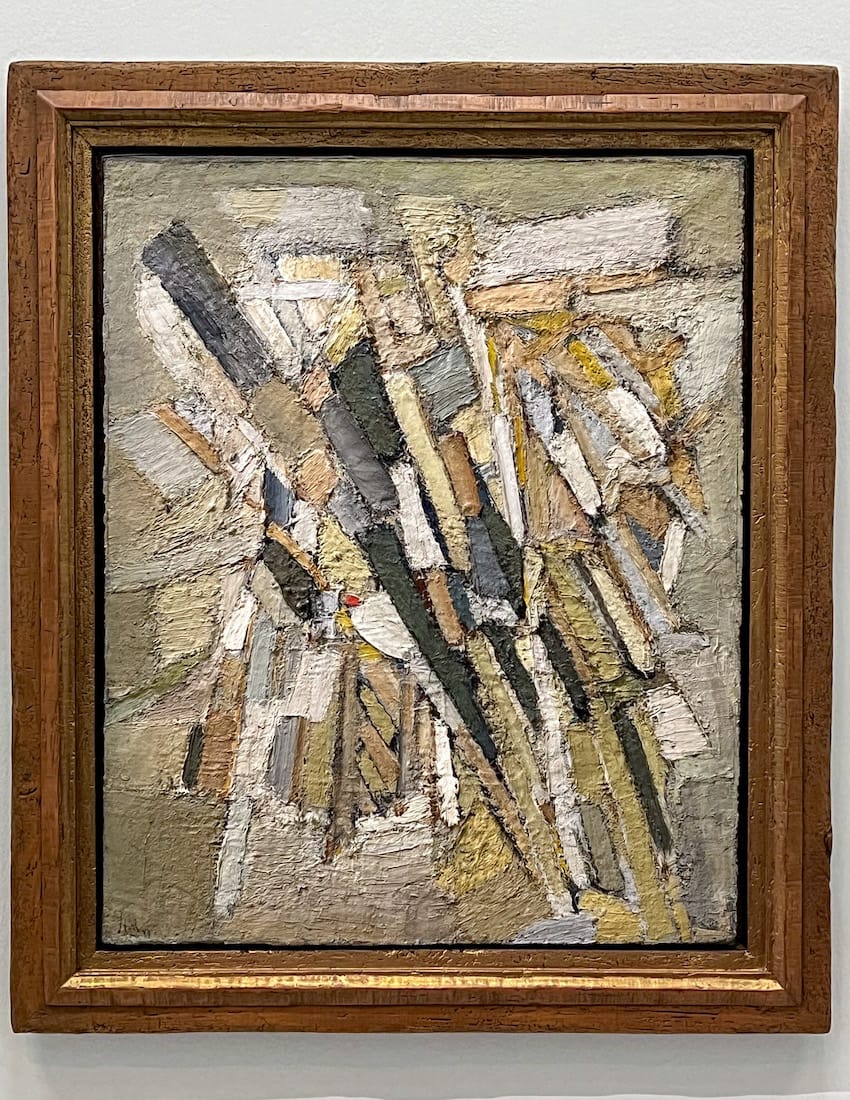

In 1950, de Staël’s work became more condensed as he superimposed thick layers of colour onto the canvas. At this time de Staël worked primarily with a knife, which is clearly visible in these paintings. After condensation, came fragmentation, with paintings consisting of coloured tesserae that are reminiscent of ancient mosaics, such as the amazing “Fugue” (1951-52). I’ve always had a love for grids and this is one of those paintings that I can keep looking at as my gaze drifts across the canvas. I also love “The White City” (1951), which reminded me of the white villages in Andalusia and which I enjoyed capturing in photographs.

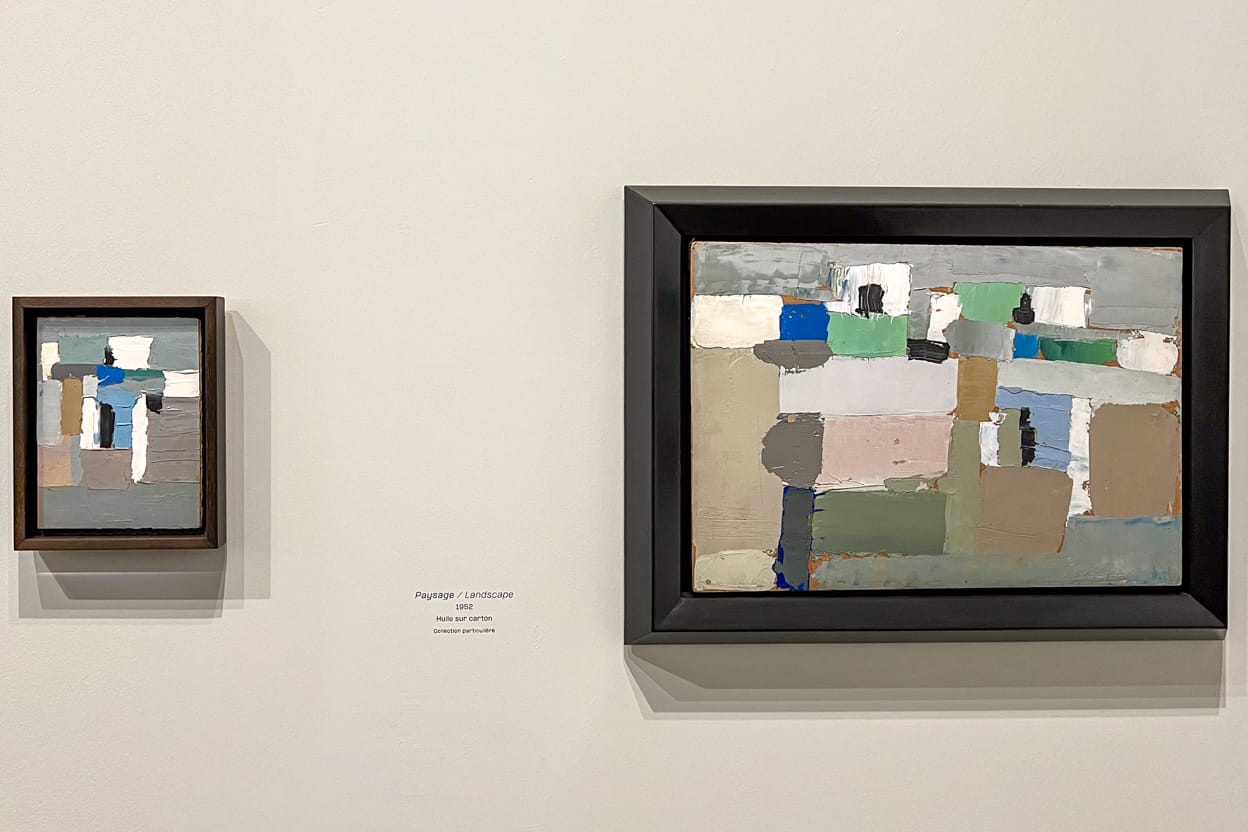

Towards the end of 1951 de Staël returned to figuration and by 1952 references to the sensory world became more explicit. He frequently left his studio to work in the open air, travelling to Normandy and the South of France, where he created dozens of small or medium sized landscapes, which strike a balance between observation and abstraction. On the evening of 26 March 1952 de Staël and his wife attended a football match between France and Sweden at the Parc des Princes stadium. It inspired him to create a series of large, colourful canvases full of life, joy and energy.

In the hands of Nicolas de Staël everything could be transformed into an abstract landscape, whether a concert, a ballet or a collection of bottles. These large canvases, which de Staël painted in 1952-53, are the highlights of the exhibition.

In the summer of 1953 de Staël, together with his family, went on a road trip to Italy, eventually ending up in Sicily. Back in his studio he transformed his impressions into a series of colourful paintings in which one can discern a field, a hill and a village, but which equally work as abstract compositions.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigento (1954) (left) and Landscape (1954) (right)

In 1953 de Staël fell in love with Jeanne Polgue-Mathieu, a married woman who lived in Nice and who did not return his love. To be near to her de Staël separated from his wife and family and rented an apartment in Antibes, where he also set up his studio. It was around this time that de Staël began painting nudes. He also abandoned his painter’s knife in favour of cotton wads and instead of applying thick layers of paint he diluted his colours. I’m afraid I agree with the friends and critics whom de Staël consulted at the time, because I don’t consider these among his best paintings.

During this time de Staël also painted various still lifes, which bear all the hallmarks of abstraction in the sense of simplification and condensation. His final painting, a splendid impression of a concert he attended ten days before he committed suicide, is a spectacular return to form. Unfortunately, it is not included in the exhibition, because it is too large to transport, so I will have to visit the Musée Picasso in Antibes one day.

I enjoyed the exhibition so much that I'm probably going to visit a second time before it closes. The last Nicolas de Staël retrospective was in 2003 at the Centre Pompidou so this is an opportunity not to be missed.

Nicolas de Staël is at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris until 21 January 2024 and at the Fondation de l’Hermitage, Lausanne from 9 February until 9 June 2024.