I was thrilled to see the M.C. Escher exhibition at the Monnaie de Paris. I am, of course, no stranger to the work of Escher—I discovered his engravings as a child and was instantly enthralled. I must have been fifteen or sixteen when I read Douglas Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach—too young to fully grasp all of its contents—which deepened my appreciation for his oeuvre. My aesthetic interests have since migrated in different directions, but Escher's work has always held a special place in my heart. Some years ago, on a trip to Andalusia, I became fascinated by the graphic patterns of the white villages cascading down the hillsides and, of course, by the mesmerizing mosaics at the Alhambra in Granada and the intriguing structure of the Mezquita de Cordoba. As I later realized, Escher had been similarly captivated by these villages and tilings. Indeed, some of his earliest prints depict hillside villages in Italy, their cubic, terraced architecture foreshadowing his later geometric explorations.

I was surprised to learn that the exhibition at the Monnaie de Paris is in fact the first major exhibition in France dedicated to the work of Escher. It took curator Jean-Hubert Martin fifteen years to convince a French institution to host the retrospective, facing systematic rejections along the way. According to Jean-Hubert Martin, the art establishment's resistance stemmed partly from Escher's status as an engraver working in a "minor genre," and partly from his unfashionable commitment to perspective in an era that prized flatness. I would add that in modern and contemporary art technical mastery has become suspect to the point where it is looked down upon with disdain.

Escher's artistic journey began inauspiciously; a sickly child who struggled at school, he excelled only in drawing and eventually mastered the art of engraving under Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita in Haarlem. He settled in Rome from 1923 to 1935, where Italian architecture and landscapes inspired his first compositions. His early work bore traces of Art Nouveau and symbolism, while already displaying an unusual approach to perspective: the Tower of Babel viewed from above, a cathedral half-submerged by waves, a recumbent statue mounted by an enormous praying mantis.

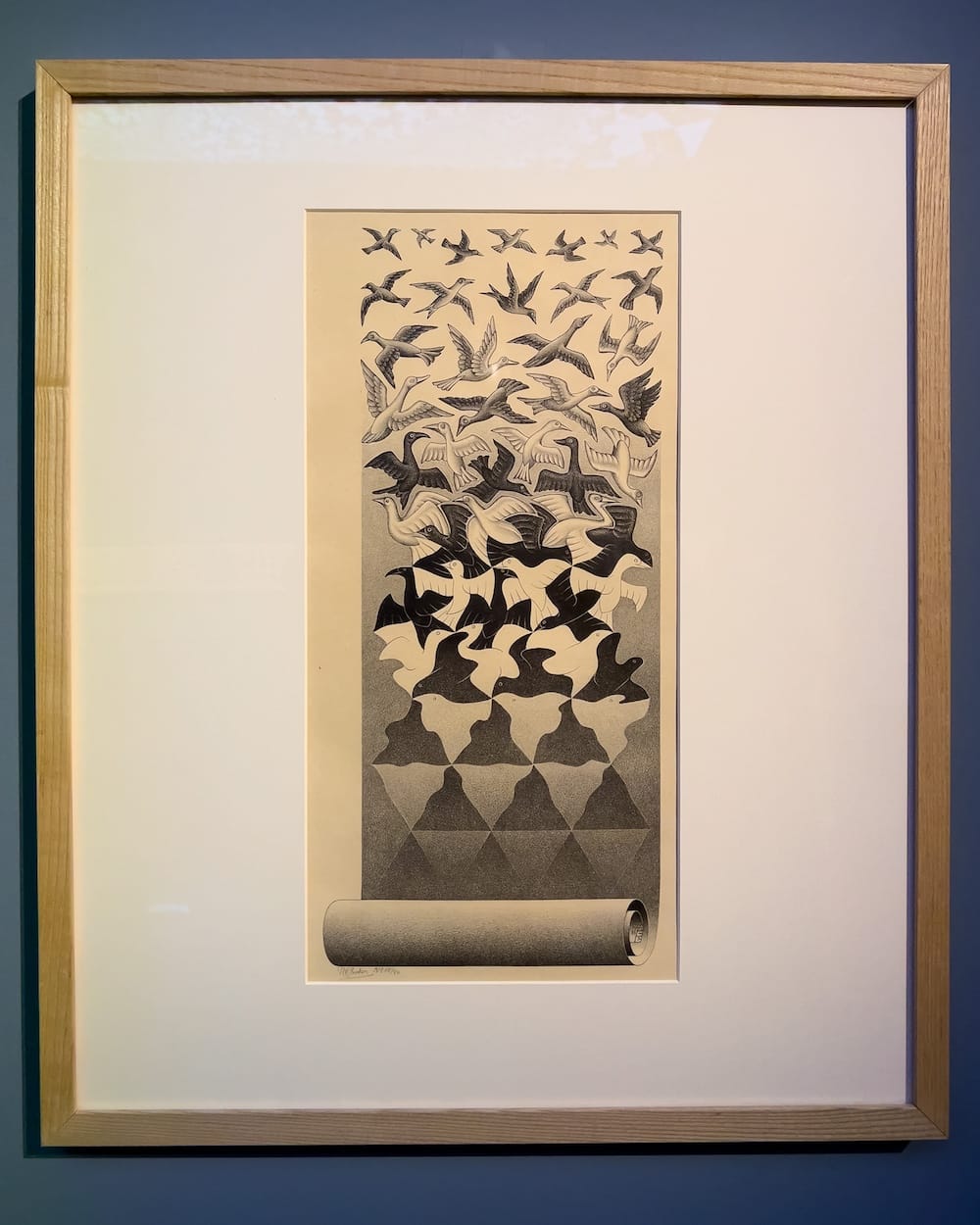

A crucial turning point in Escher's artistic development was his second trip to southern Spain in 1936. He became fascinated by the tessellations that decorate the Alhambra and the Real Alcazar de Sevilla: geometric patterns based on triangles, squares, or hexagons that are repeated like tiles to cover a plane without leaving gaps. Upon his return he approached his half-brother Bernd, a crystallography professor, who introduced him to the mathematical work of Evgraf Fedorov and György Polya who demonstrated that only seventeen symmetries can tile a plane. Escher went on to produce a large number of ever more intricate tessellations of interlocking horsemen, salamanders, and birds that shift between positive and negative space with mesmerizing precision.

Though marginalized by the art world, Escher has long captivated scientists and mathematicians who recognized the profound geometric principles underlying his work. A small exhibition during the 1954 International Congress of Mathematicians in Amsterdam caught the attention of the mathematician H.S.M. Coxeter, who specialized in geometry and who asked him if he could use two of his drawings to illustrate one of his research papers. Coxeter subsequently sent Escher a copy of his paper, which introduced him to the world of non-Euclidean geometry. Though he never grasped the theoretical underpinnings, Escher taught himself to render these concepts visually, producing works like "Circle Limit" that represent infinity within a bounded disk.

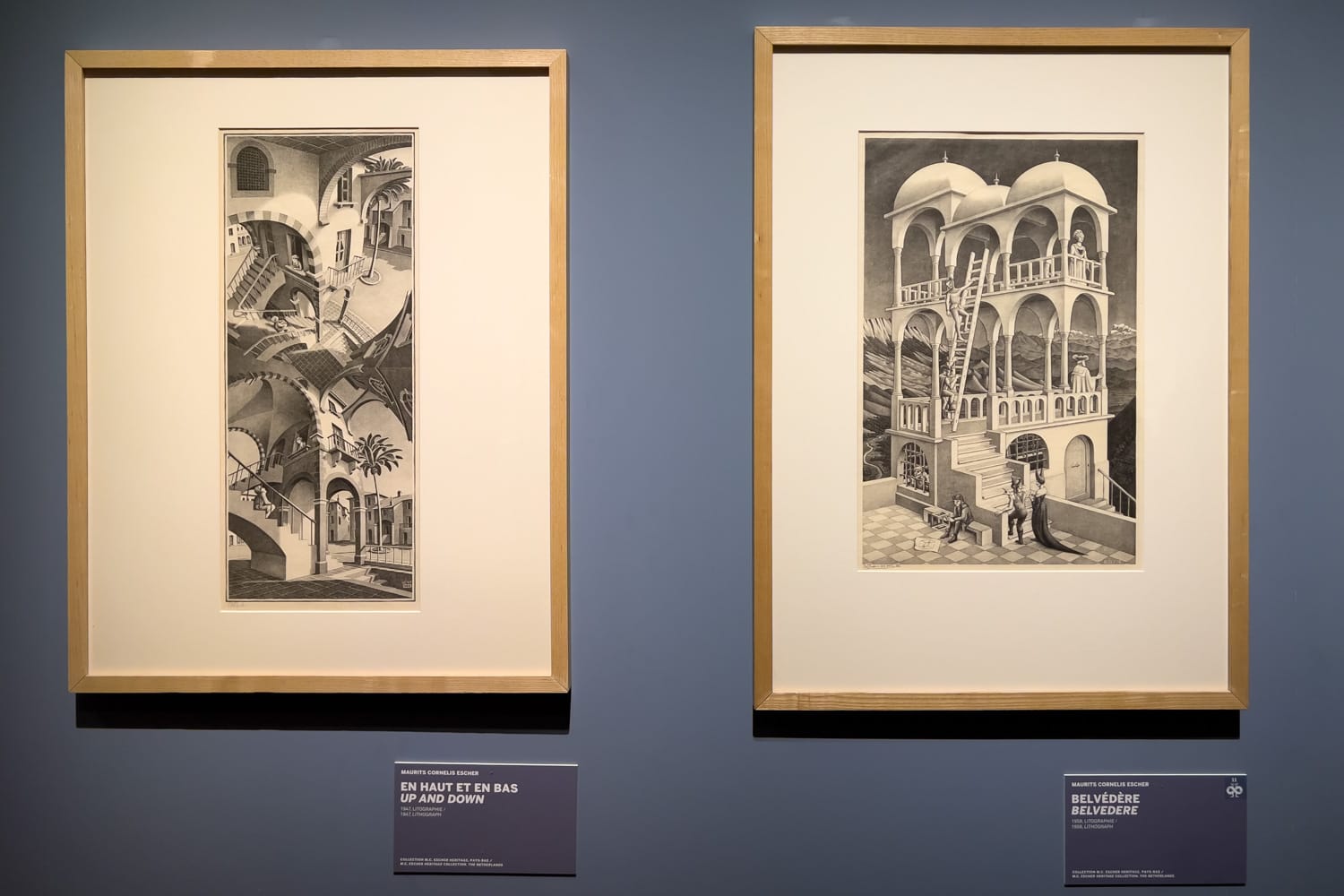

The exhibition brings together over 170 original works including classics such as “Ascending and Descending” (1960) and “Waterfall” (1961) as well as various works that I didn’t recall having seen before. “Liberation” (1955) is a new favorite of mine.

Escher's influence has rippled far beyond science and mathematics into popular culture, inspiring album covers, comic books, and animated television shows including an episode of The Simpsons.

The Monnaie de Paris retrospective vindicates an artist who, by refusing to follow modernism's dictates, created a singular body of work that deserves a wide audience.

M.C. Escher is at the Monnaie de Paris until 1 March 2026.