I only occasionally read biographies, because it is the work that matters to me, and not the life of the artist, scientist or philosopher who created it. However, a good biography illuminates the work and the context in which it was created.

I’ve always liked the work of Vincent van Gogh, or at least the paintings he made after he had moved to France, but in recent years I’ve come to love his work. After reading a rave review of Van Gogh and the Artists He Loved by Steven Naifeh I learned that Naifeh, together with Gregory White Smith, had written the definitive biography of Van Gogh, at least according to Leo Jansen, curator at the Van Gogh Museum, and he should know.

Van Gogh. The Life is a monumental achievement. It was ten years in the making and in their undertaking the authors were assisted by of a team of researchers and translators. The authors draw heavily on the six-volume illustrated and annotated edition of Van Gogh’s letters, which was published in 2009. At more than 900 pages Van Gogh. The Life is a lot of Van Gogh, but it reads like a novel.

I thought I knew everything I needed to know to appreciate Vincent van Gogh's work. As it turns out there is a lot that I didn’t know and I now appreciate his work even more. I had never noticed that on one of the fishermen’s boats in Fishing Boats on the Beach at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (1888) it says “amitié” (friendship) and that this is a reference to Van Gogh’s brother Theo. Of course, this also shows that I didn’t look closely enough at the painting or else I might have noticed this myself, but even then I still would not have known that Van Gogh added the word “amitié” at a later stage, when the painting was already finished. This is precisely why Van Gogh. The Life is a great biography: it is an invitation to go back to the work and look more closely. I have now also bought Van Gogh. The Complete Paintings.

To say that Van Gogh was a difficult person is an understatement. I didn’t know how much of a burden Van Gogh was on his family and of course on himself. I didn’t know either that for a short while he aspired to become a teacher and even spent a couple of months as an assistant teacher at a school in Ramsgate, a seaside town in the UK. I knew that he had toyed with the idea of becoming a pastor, but I didn’t know that he actually prepared for and failed the University of Amsterdam theology entrance examination.

Reading about Van Gogh’s doomed ventures and his bouts of self-chastisement, especially during his time as a missionary in a coal-mining district in Belgium, is almost painful. I realized that his life could have turned out differently. Indeed it could have ended prematurely, before he discovered art.

I somehow always thought that Van Gogh was primarily self-taught. I didn’t know that in November 1880, upon his brother Theo’s suggestion that he take up art in earnest, Van Gogh registered at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. In the following year he took up an apprenticeship with his second cousin Anton Mauve, at the time a successful artist in The Hague. But before long he and Mauve fell out.

I didn’t know either that Van Gogh was an avid reader, but it doesn’t surprise me. He begged his brother to send him all the latest books about art and colour theory. After reading a book by the French art critic Charles Blanc, Grammaire des arts et du dessin (1867) Van Gogh went on to advocate the use of complementary colours with religious zeal.

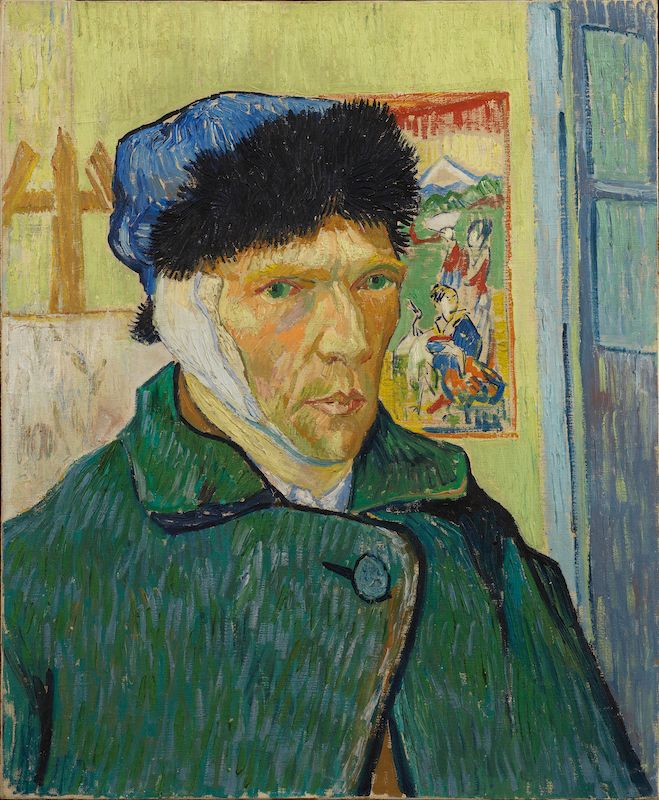

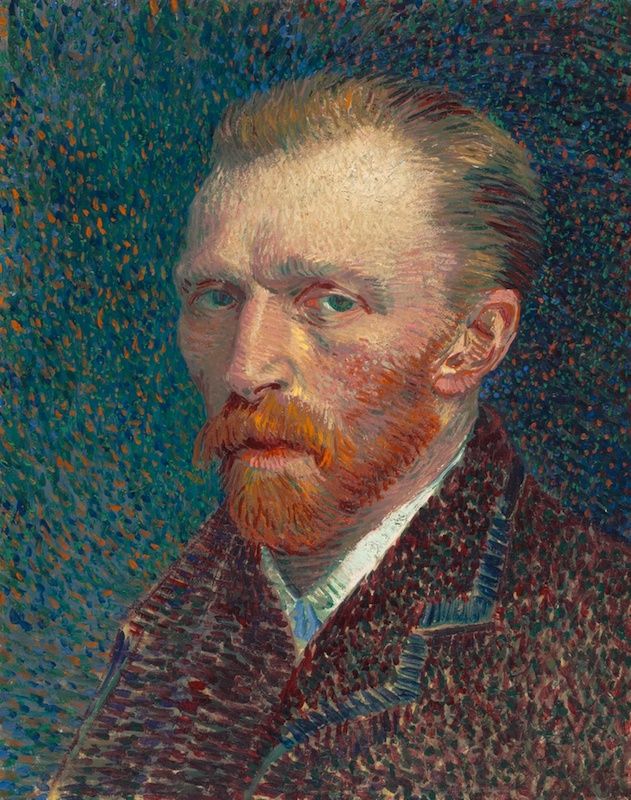

I also didn’t know that there were periods in his life when Van Gogh spent copious amounts of money on fancy clothes. Fancy clothes? Van Gogh? Again, I could have known had I looked more closely at some of his self-portraits in which he portrays himself as a gentleman in a suit and tie.

I still find it striking how Van Gogh developed as an artist in little more than ten years. From 1883 until 1885 he lived with his parents in Nuenen, where he created nearly 200 oil paintings, including The Potato Eaters (1885), and countless drawings and watercolours. During this period his palette consisted of dark earth tones. For years his brother had encouraged him to make landscapes, but Van Gogh persisted in his endeavour to make portraits. I tend to agree with Naifeh and Smith that the portraits from this period are not among his best.

November 1885 Van Gogh moved to Antwerp where he was briefly hospitalized and where, in January 1886 he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. But by March he had already fallen out with one of the teachers, upon which he travelled to Paris and moved in with his brother Theo, by then a successful art dealer.

Naifeh and Smith describe in great detail the circumstances of Van Gogh’s life in Paris, from the places he frequented to the people he met. His brother’s urging notwithstanding Van Gogh was slow to change his ways. It wasn’t until he moved to Paris that Van Gogh adopted a brighter palette. It was at this time too that Van Gogh finally worked out how to put the theory of complementary colours into practice. In Antwerp Van Gogh had become interested in Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which he began to collect in Paris while adopting various style elements in his own work. In 1887 he began to experiment with pointillism, which he quickly abandoned in favour of what would become his trademark brushstrokes.

In February 1888 Van Gogh moved to Arles. Van Gogh realized that staying in Paris any longer would exhaust both himself and his brother. In less than two years he produced around 200 paintings, including some of his most beloved works, The Yellow House, Bedroom in Arles, Café Terrace at Night, Sunflowers and The Night Café. In May 1889, after suffering a severe nervous breakdown, Van Gogh entered a mental hospital housed in a former monastery in Saint-Rémy, some 30 kilometers from Arles. Here he created one of his most famous paintings, The Starry Night, and a number of paintings of the olive groves near the hospital. Upon learning that Jo Bonger, Theo’s wife, had given birth to a son, he painted one of my favourite paintings, Almond Blossom.

In May 1890 Van Gogh left the hospital in Saint-Rémy and moved to the Paris suburb of Auvers-sur-Oise to be near to his brother and Dr Paul Gachet, a doctor who had treated various other artists. It was here that Van Gogh died, on 27 July 1890.

It is commonly believed that Van Gogh committed suicide. This fits with the myth of the tormented artist, the genius, unrecognized in his lifetime, who finally succumbs to madness. In a lengthy appendix Naifeh and Smith put forth an alternative theory. As they point out there are various issues with the suicide hypothesis from the angle of the shot to the disappearance of the gun and Van Gogh’s painting equipment and the distance the wounded Van Gogh would have had to cover to get back to his lodgings had he shot himself in a field. Instead Naifeh and Smith propose that Van Gogh was shot by a local teenager, René Secretan, who, together with his friends, used to bully Van Gogh. In their telling Secretan fired the gun from a distance, without intending to kill Van Gogh. Once they realized what they had done the kids threw Van Gogh’s painting equipment into a nearby river and quickly left town. In the 1930s villagers already told art historian John Rewald that Van Gogh had been shot, but at the time no one verified the rumors.

I like to believe that Van Gogh was killed by accident. Not that it makes any difference. But somehow I find that theory more comforting than the standard account.*

It is obvious that Vincent van Gogh had a troubled life. What stands out in Naifeh and Smith's biography is his tenacity, his struggle to persevere against the odds and his eagerness to learn. After reading Van Gogh. The Life I admire Van Gogh all the more.

* Note that the British Van Gogh specialist Martin Bailey disputes the hypothesis put forth by Naifeh and Smith in his book Van Gogh’s Finale. Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (London: Frances Lincoln, 2021).