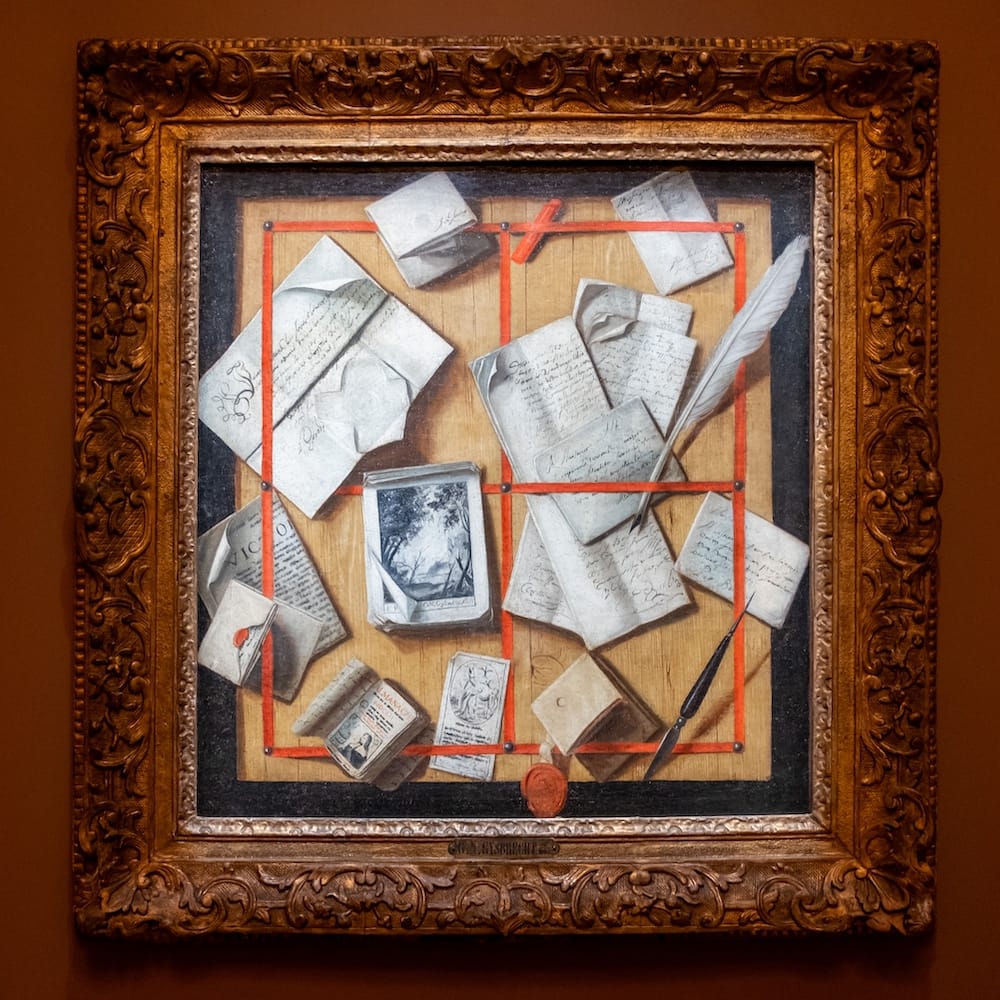

Cristoforo Munari, Trompe l'oeil aux instruments du peintres-graveuses et aux gravures (1715) (left) and Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, Trompe l'oeil (1665) (right)

In his Natural History the Roman author and philosopher Pliny the Elder (23/24-79) recounts the tale of the ancient Greek artists Zeuxis and Parrhasius who once staged a contest to determine who was the greater artist. Zeuxis had painted a bunch of grapes which appeared so realistic that birds descended to try and eat them. Both artists then walked to Parrhasius’s studio where Zeuxis asked Parrhasius to remove the curtain so that he could see his painting, only to discover that the curtain itself was the painting. Zeuxis acknowledged his defeat, for while he had deceived the birds, Parrhasius had deceived him.

The legend of Zeuxis and Parrhasius lives on in the tradition of the trompe l’oeil painting. The term trompe l’oeil was coined by the French artist Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761-1845), himself one of the great masters of the genre, but its history can be traced back to the 16th century and all the way to antiquity where it was employed in murals to suggest a window or a door.

To celebrate its 90th anniversary the Musée Marmottan Monet has organized an exhibition tracing the history of the trompe l’oeil painting from the 16th century to the present. Jules and Paul Marmottan were fascinated by the trompe l’oeil and the Musée Marmottan Monet holds some fine examples of the genre, which were restored for the occasion.

The exhibition is divided into eight sections, which illustrate in a chronological fashion the evolution of the trompe l’oeil genre over time. From the 16th century onwards, the art of trompe l’oeil followed precise rules: the painting had to fit in with the surroundings, the objects represented in the painting had to be shown in their actual size and the artist’s signature had to be hidden so as not to break the illusion.

Painters created trompe l’oeil paintings to show off their skills and also just for the fun of it. At least, walking around the exhibition I got the impression that these 17th and 18th century artists must have enjoyed fooling the audience.

The exhibition opens with a painting by Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts (1630-c.1675), one of the other grand masters of the genre, and a fascinating panel by Cristoforo Munari (1667-1720). Both paintings illustrate one of the recurring motifs in trompe l’oeil, that of objects, notes and drawings strapped to a faux woodgrain surface. To enhance the illusion Munari even attached a stick to the panel.

Gaspard Gresly, Trompe l'oeil (left), Detail of a Gaspard Gresly, Porte de bibliothèque (1750) (middle), Louis-Léopold Boilly, Un trompe l'oeil (c. 1800-1805) (right)

Trompe l’oeil painters went to great lengths to simulate wood in all its peculiarities of knots, grain, and splits. During the 18th century painters such as Louis-Léopold Boilly and Étienne Moulineuf added another motif by creating the illusion of a broken glass frame covering the painting. Depending on your angle of view some of these shattered glass paintings work exceptionally well.

In the 19th century the practice of trompe l’oeil enjoyed a revival in the United States among painters of the so called Philadelphia School, but they never achieved the mastery of their 17th and 18th century European predecessors.

Today, the tradition of trompe l’oeil lives on in the “tableaux pièges” (or snare pictures) of Daniel Spoerri and in the hyper-realist sculptures and installations of artists such as Daniel Firman, whose “Jade” (2015) could be mistaken for a teenage girl leaning against a wall.

"Trompe-l’oeil, from 1520 to the present day" is a fun and instructive exhibition. It had never occurred to me that the depiction of bunches of grapes in 16th and 17th century still lifes is an indirect reference to the myth of Zeuxis and Parrhasius.

Trompe-l’oeil, from 1520 to the present day is at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris through 2 March 2025.

More trompe l’oeil:

The Eye Deceived. Painted Illusions by Cornelius Gijsbrechts.

Links:

A few years ago The Metropolitan Museum in New York organized an exhibition exploring the connections between Cubism and the trompe l’oeil tradition