Every few years the Louvre organizes an ambitious thematic exhibition. I still have fond memories of Les Choses, an exhilarating exploration of the still life from antiquity to the present day. This time around the Louvre has dedicated an exhibition to the figure of the fool (French: fou or bouffon; German: Narr; English: jester, joker or fool; Spanish: bufón). The organizers of the exhibition have unearthed a wealth of material, - paintings, sculptures, books, costumes and historical artifacts -, which show the representation of the fool from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.

The exhibition opens with a number of fabulously illuminated books of hours. In the medieval world, the fool represented the person who refused to acknowledge the existence of God. For as it says in Psalm 52/53: “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God’.” In the early Middle Ages, as the practice of decorating a manuscript with elaborate flourishes and illustrations in the margins became more widespread, artists began to depict the fool in illuminations of the initial “D” of Psalm 52/53 “Dixit insipiens in corde suo: non est Deus.” Over time the figure of the fool who rejects God became increasingly codified with torn or parti-coloured clothes and a stick in one hand and a piece of bread or cheese in the other. At some point the fool jumped off the page and entered the church, as illustrated by various sculptures on display.

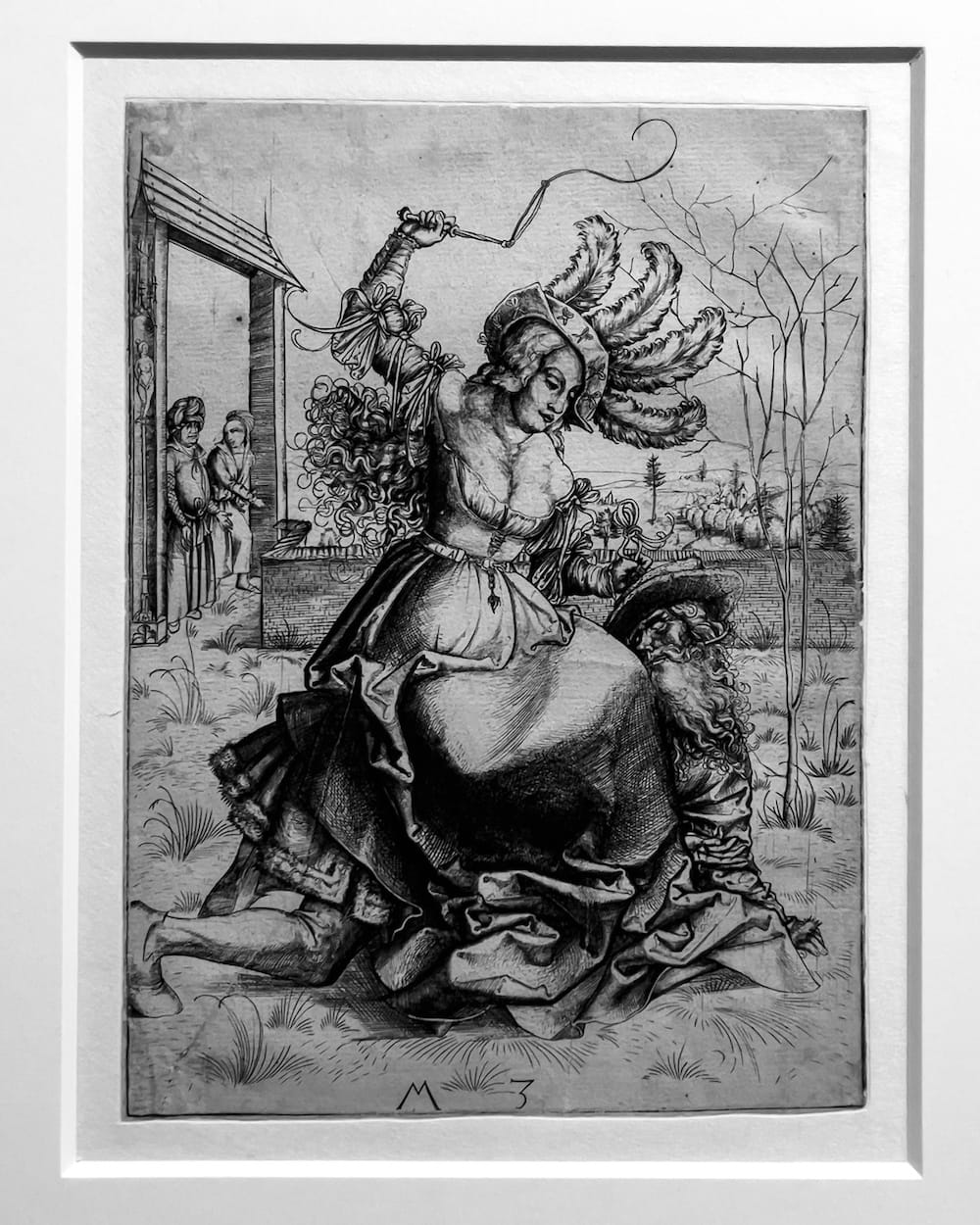

In the Middle Ages love was considered a folly that deprived man of his self-possession. It was a common theme in medieval romances, in which the hero was seized by madness, as in the legend of Tristan and Isolde and the tale of Lancelot. In the late 14th century numerous engravings and sculptures appeared depicting Aristotle acting like a fool as he was blinded by his love for Phyllis, the beautiful mistress of Alexander the Great.

Master MZ, Aristotle and Phyllis (c. 1500) (left) and Master of the Banderoles, The Fountain of Youth (c. 1475-1500) (right). Notice the jester in the top right corner. I still find it odd that these images were popular in the late 15th century.

At around the same time the fool appeared as a sassy observer in images heavy with symbolism depicting fortune tellers, brothels and the garden of love, which to a contemporary viewer would have been easy to decipher. The fool was at once a symbol of lust and a commentator denouncing debauchery and depravity. Some engravings from this period are, well, rather curious, to say the least.

In medieval times many royal courts across Europe employed professional jesters, some of whom may have been intellectually disabled while others played the fool. Some jesters rose to international fame, much like the comedians of our times, and were immortalized in portraits. The court jester is in fact a universal figure. In some form or another he can be found in China, India, the Americas and Africa (*). Some royals themselves descended into madness, such as Charles VI (1368-1422) and Joanna the Mad (1479-1555).

At the beginning of the Renaissance, the figure of the fool became more common. Fools showed up everywhere: on tapestries, as a chess piece (in French the bishop is called “fou”) and on tarot cards, the earliest of which date back to the 15th century and are displayed in the exhibition.

In 1494, the German humanist scholar Sebastian Brant (1457/58-1521) published The Ship of Fools, a satirical allegory in which he took aim at the vices of his time. At around the same time the Dutch humanist, theologian and philosopher Erasmus (1466-1536) published The Praise of Folly (1509), a satirical essay in which he takes swipes at all aspects of life and society. Both books became huge bestsellers and were translated into multiple languages. The exhibition includes a first edition of both works, which in itself doesn’t add much, - you would have to read them to learn more about the content -, but it was interesting to see a “hybrid” edition of the French translation of The Praise of Folly with illustrations of Brant’s Ship of Fools, attributed to Albrecht Dürer.

“The Ship of Fools” would become a popular metaphor to describe the disorder of the world. The painting by Hieronymus Bosch commonly known as “The Ship of Fools” was not directly inspired by Sebastian Brant’s book. It is part of a triptych of which the centrepiece is missing. It is a marvelous painting and shows a group of people feasting aboard a tiny ship. Clearly visible by their attire are a priest and a nun. A jester can be seen sitting on the branch of a tree set on the ship’s deck. In a world overcome by vice and folly, the jester has no more lessons to give.

In the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525/30-1569) the fool receded to the background and became a witness of humankind’s follies. It is worth emphasizing that at the time human foolishness was seen first and foremost in moral terms. A fascinating engraving by Pieter van der Heyden (after Pieter Bruegel the Elder) shows a number of human figures dressed in clothes emblazoned with the word “Elck” for everyman, obsessively pursuing material goods. In the background a picture with the legend “No one knows himself” shows a jester looking at himself in a mirror.

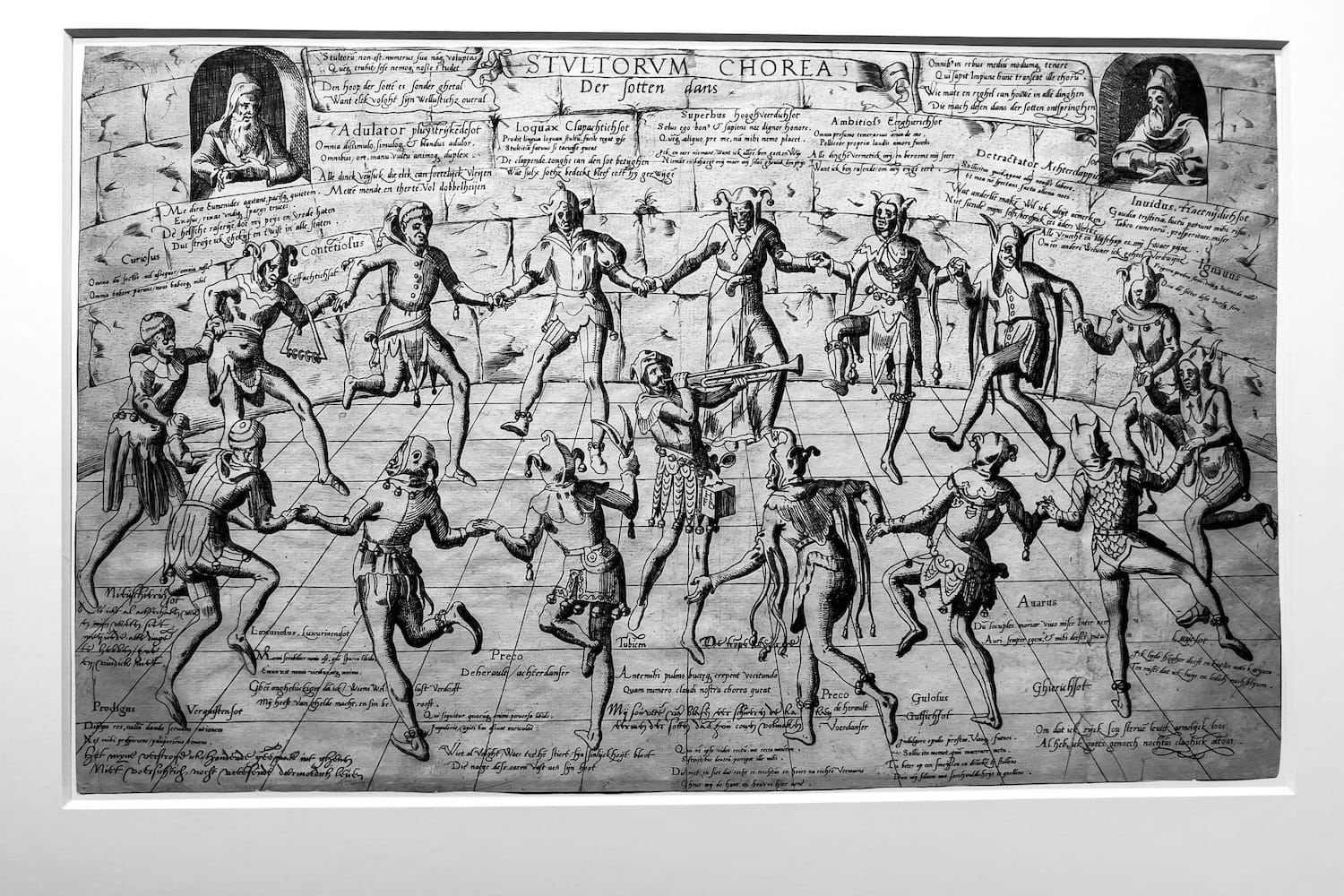

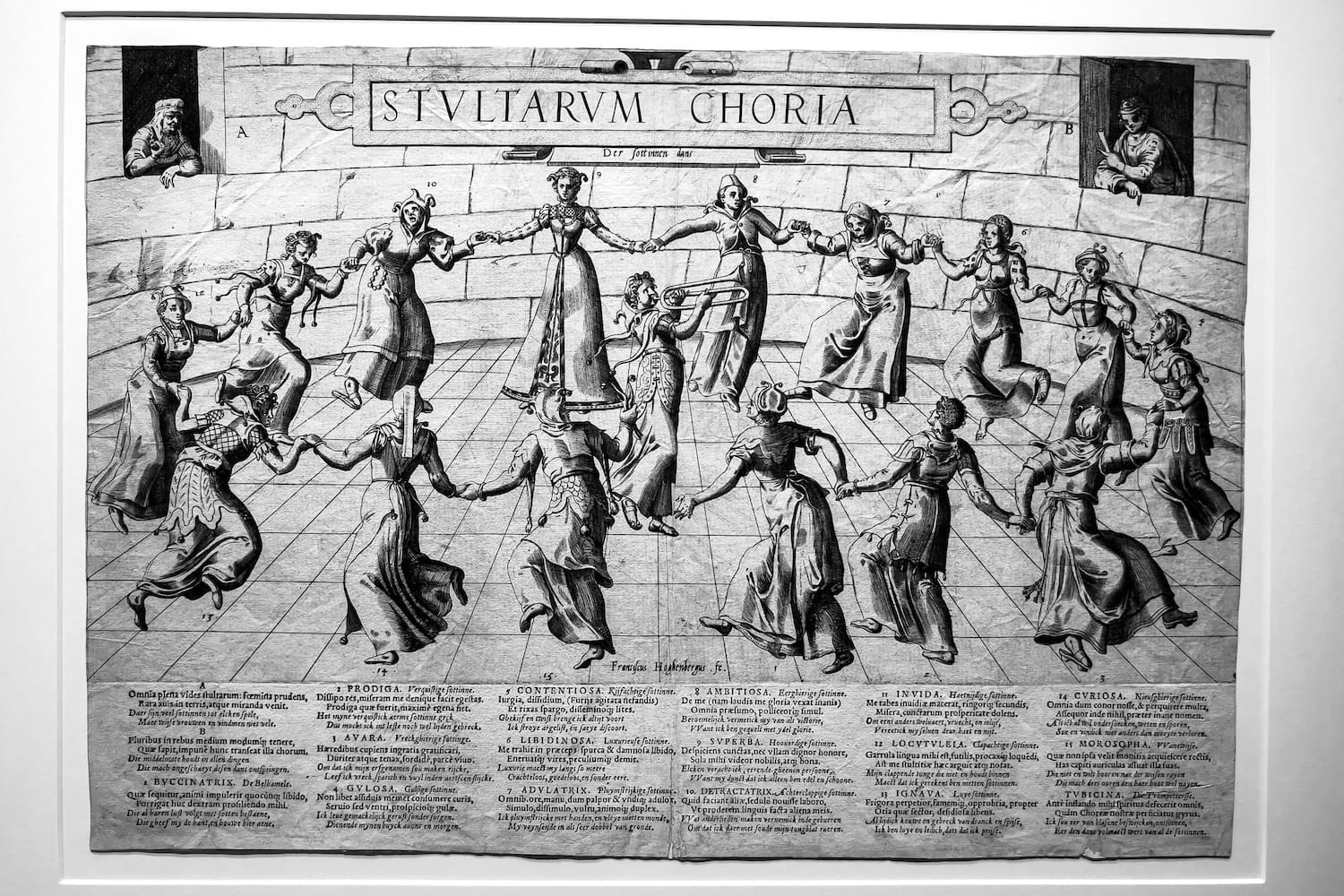

Frans Hogenberg, The Dance of Fools (c. 1560-70)

This moral dimension is also illustrated by two other intriguing engravings, “The Dance of Fools” and “The Dance of Foolish Women” (c. 1560-70) by Frans Hogenberg (c. 1539/40-1590), which show fifteen figures dressed as jokers (male in one picture, female in the other) dancing around in a circle, with each figure associated with a vice or flaw, as described in the picture’s extensive legend.

In the late 17th and early 18th century, reason banished the fool from the world of images and the jester as a court institution vanished from the stage. The figure of the fool lived on in literary figures such as Don Quixote, Yorick, Pulcinella and Rigoletto.

Francisco Goya, Yard with Lunatics (1794) (left) and Gustave Courbet, The Mad Man with Fear (1844) (right)

The fool resurfaced in a different guise in the late 18th and early 19th century with the birth of psychiatry and a renewed interest in Medieval and Renaissance art. Francisco Goya’s haunting “Yard with Lunatics” (1794) shows a hospital scene, which he himself witnessed while being treated for an illness that left him deaf. Also included is Johann Heinrich Fussli's (1741-1825) famous painting of "The Sleepwalking Lady Macbeth" (1784). This final part of the exhibition feels a bit like an afterthought (much like this paragraph) and would have warranted an exhibition in itself.

The exhibition ends with an amazing self-portrait by Gustave Courbet, “The Mad Man with Fear” (1844), in which he shows himself dressed in what looks like a jester’s costume, grasping his head while balancing on the edge of an abyss. It is a powerful representation of self-doubt and inner torment.

“Figures of the Fool” is a fascinating exhibition. I didn’t know that the fool or the joker has such a rich cultural history. To get the most out of the exhibition you really need to read the section introductions and the caption of each work. And of course you should not forget to also closely examine the works on show.

Figures of the Fool. From the Middle Ages to the Romantics is at the Louvre in Paris until 3 February 2025.

(*) Beatrice K. Otto, Fools Are Everywhere. The Court Jester around the World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001.